During the two-month-long summer vacation, our family of three (me, my mom, and my sister) would head to Calcutta with bags filled with clothes, gifts, and homework copies like a ceremonial ritual performed annually.

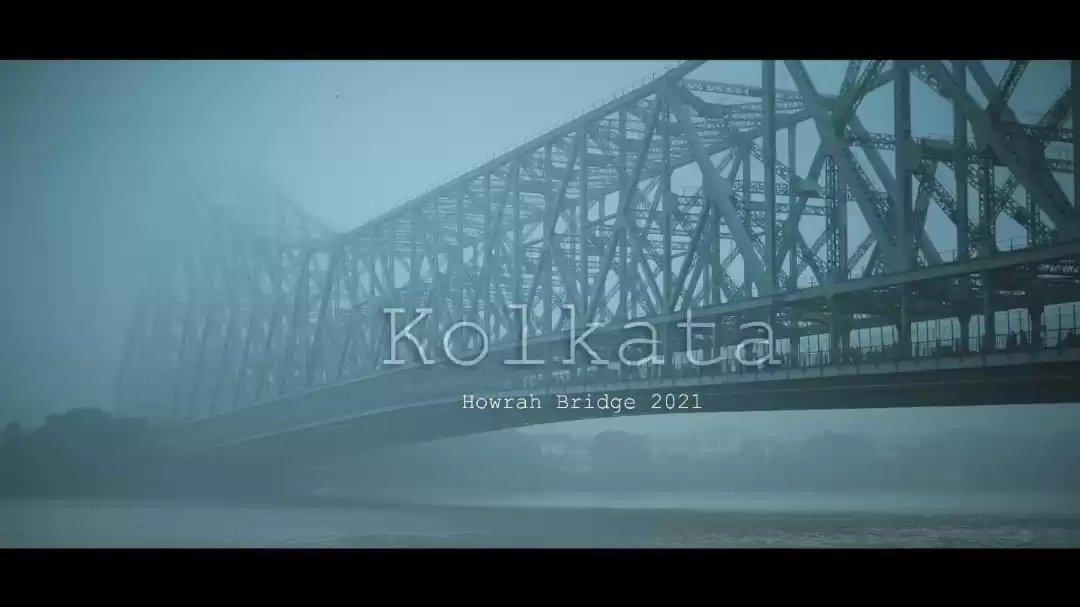

As the train reaches Lilooah Carriage, three miles from the final destination, the coachman halts testing our patience as the train waits for a signal from the headquarter. As it starts moving slowly over the mesh of entangled tracks, Calcutta welcomes you with shiny steels of the cantilever bridge swaying before the blue evening sky. My sister and me, with our faces affixed to the window bars and necks squeezed would look at the parts of the mammoth and iconic construction awestruck.

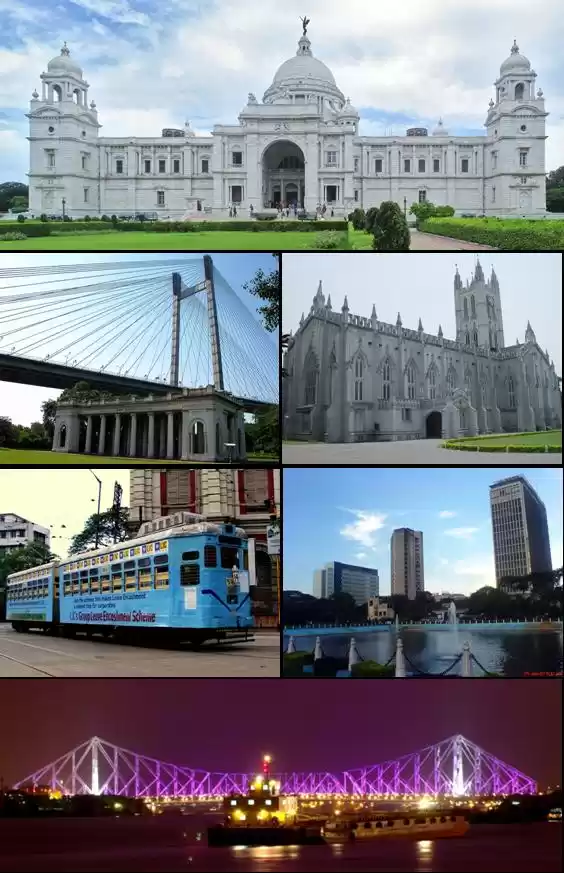

No other city that I have travelled so forth, except Jaisalmer, welcomes you with such grandeur.

Over the Bhagirathi-Hooghly River, traditionally known as 'Ganges', the 205-meter long bridge is made with 26,500 tons of high tensile alloy steel and painted in chrome oxide connecting Haora (or Harirah) to Mullick Ghat of Sutanati (the modern-day Calcutta).

On June 1851, George Turnbull, the Chief Engineer of East India Railways submitted the first plan for Howrah Station, and the first locomotive left the station on 18 th June 1853. By the turn of the century, however, as trade and passenger services through railways rise, Harley Ricardo-the British architect famed for using glazed tiles and piers received the contract in 1905 to built the Howrah Station, a spacious columnar structure made of red bricks with six platforms (now expanded to fifteen) on the western banks of Hooghly River.

There was no landing ghat on the Howrah side. Passengers from Sutanati had to go to Armenian Ferry Ghat, a creek of Strand Road just opposite the Howrah Tram Depot. At the eastern riverbank, passengers "had to jostle their way through the 'exciting' crowd to the 'Booking Window' that issued tickets which includes fare of crossing the river to arrive at the provisional rail platform consisting of a tin shed.

Given the increasing traffic and transport of ships and passengers, the Port Commission formed in 1870 that first construct a pontoon (or floating) bridge designed by Sir Bradford Leslie but didn't last long. A shipwreck, a cyclone, and occasional careless stepping and footfall led baboos to think for a permanent replacement.

The Port Commission thus formed a committee that mulls over the different idea before agreeing to the construction of an iron bridge-sturdy, durable, and everlasting as the replacement to the pontoon bridge. Sir Rajendranath Mookherjee, an industrialist and founder of Indian Statistical Institute, recommended for an iron-made suspension bridge that periodically unfastened to allow the passing of steamers and marine vehicles first, during the daytime and later in the night. The five kilometres long, sludgy Strand Road, the only thoroughfare stretched from Ahirtola Burning Ghat on the north to Prinsep Ghat in the south was illuminated with brightest gas lights and later electric lamp posts for ease of passing.

Thus, in 1930 the construction of Howrah Bridge begins and continues amidst the seven-years of World War (1938-1945) and finally completed in 1942. Designed by one Mr Walton of M/s Rendell, Palmer & Triton, Tata Steel supplied the alloy steel needed for building the bridge to M/s Cleveland Bridge & Engineering Company [contract scrapped] and later, Braithwaite, Burn & Jessop Construction Company awarded for the erection and engineering works of the bridge.

The entire project cost approximately 25 million Indian Rupees (£2,463,887) and stands the sixth-largest cantilever bridges in the world with a recorded population of 150,000 pedestrians and 100,000 vehicles commuting over it, every single day. The bridge deck hangs from panel points in the lower chord of the main trusses with 39 pairs of hangers.

The roadways beyond the towers are supported from ground, leaving the anchor arms free from deck load. Instead of nuts and bolts that otherwise used for the bridges, the Howrah Bridge has none but formed by riveting the whole structure.

The iconic bridge now stands as a gateway to Calcutta for millions of passenger especially, from southbound and towns of Howrah, Bardhaman, Durgapur and other north-central states of India come to Calcutta. Get into one of the pot-bellied yellow ambassador cars with deep headlamp cowls from Hindustan Motors-another Calcutta signature from the prepaid booking counter outside the Howrah Station.

The driver steers through the crowded and mutinous lanes of the Station Road passing by Chandmari Ghat heading towards Howrah Bus Depot. Before alighting through the western mouth of Howrah Bridge, the yellow ambassador does a cryptic roundabout of Netaji Subhas Bose statue near Gulmohar quarters. As the taxi struggle the traffic over the 700m long bridge, sneak your head out the window [with caution] to look at the zigzag knitted heavy iron beams overhead. Even in the furthest confines of one's fanciest of dreams, one cannot gauge its enormity looking at its photographs or even travelling over it.

For nearly twenty years or more, every time I travel between the two 270-feet tall vertical towers that support the bulk of iron seem to be rising through the clouds with a line of yellow taxis and red-green buses furiously whizzing past in every possible direction; I find there's still something about the bridge that remains un-captured.

It's difficult to capture the quintessential eternal essence of Calcutta fully and always.