This story is about Tsewang Paljor, the most famous dead body that lies on Mount Everest.

“He has pulled his red fleece up around his face, hiding it from view, and wrapped his arms firmly around his torso to ward off the biting wind and cold. His legs stretch into the path, forcing passers-by to gingerly step over his neon green climbing boots.”

Most people who encounter him know him only as “Green Boots”. For nearly 20 years, his body, located not far from Mount Everest’s summit, has served as a grim trail marker for those seeking to conquer the world’s highest mountain from its north face. Many have lost their lives on Everest, and like Paljor, the vast majority of them remain on the mountain. But Paljor’s body, thanks to its prominence, came to be one of the most well-known.

About 80% of people also take rest at the shelter where Green Boots is, and it’s hard to miss the person lying there.

Rachel Nuwer from BBC news investigates the sad and little-known story behind its most prominent resident, ‘Green Boots’ – and discovers the disturbing effects this deadly mountain can wreak on the mind and body.

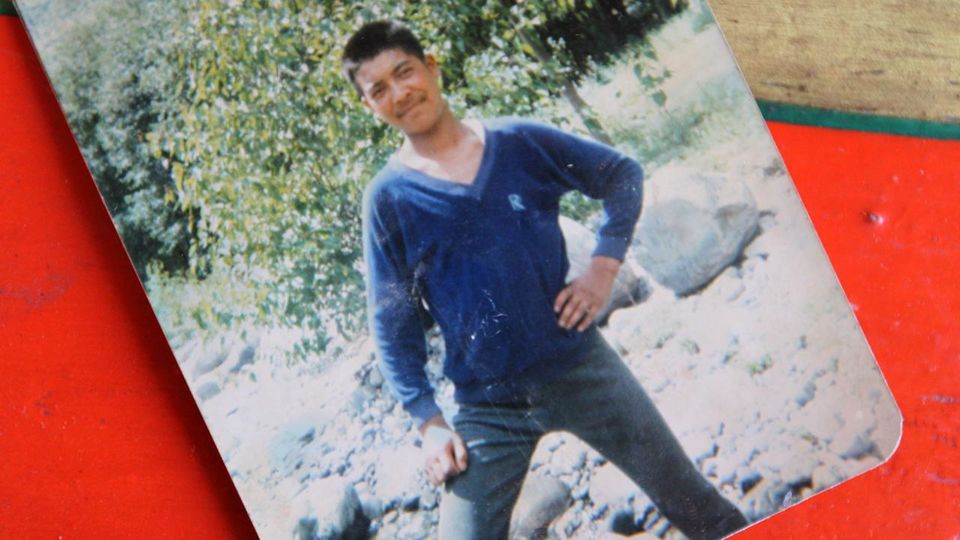

She, along with Tsultim Dorjey, a sociologist and guide, headed to Paljor’s hometown, Sakti. They met Tashi Angmo, Paljor’s mother, who opened the door. At 73, her twinkling eyes and smiling face appeared a decade younger. Radiating grandmotherly warmth, she greeted them energetically – “Julay!”

A quiet middle child with five siblings, Paljor was known in the village for his polite, compassionate manner. Though good-looking, even as a teen Paljor never had a girlfriend – he was simply too shy. He once told his brother that he was more interested in dedicating his life to something bigger than himself than in getting married.

After completing 10th grade, he quit school and tried out for the Indo-Tibetan Border Police (ITBP), whose sprawling campus was located in nearby Leh, Ladakh’s dusty capital. To Paljor and his family’s delight, he made the cut.

Tashi Angmo was very supportive of his position at the ITBP, but he sensed that her support would only extend so far – certainly not to the top of the world’s highest mountain. So when he was selected to join an elite group of climbers who would undertake a risky but grandiose mission – to become the first Indians ever to summit Everest from its north side – he chose not to reveal his true destination to her. “He told a small lie, that he was going to climb a different mountain,” his mother says. “But he also told some friends what he was actually doing, and word got back to us.”

Commandant Mohinder Singh, who led the team, recalls Paljor as being very talkative, “like a child,” and that he loved to attempt difficult rock climbs. “He looked like a monkey when he climbed,” Singh said. He also remembers Paljor’s love of roast chicken; his tendency to sing in his free time; and that he was always volunteering to take on difficult jobs. “He was very helpful like that,”

The problems started on the morning of 10 May, 1994, when the team was delayed by strong wind and then overslept. They did not set out from Camp VI until 08:00, rather than 03:30 as planned. Given the extremely tardy start, they decided to move further up the mountain to fix ropes rather than attempt the summit, since doing so would guarantee descending through the Death Zone in the dark – the area above 8,000m where climbers often lose their lives.

By 14:30, the team had made significant progress, but the wind had begun to pick up again. Singh had given the team strict orders to turn around at 14:30, or 15:00 at the latest. Harbhajan Singh, however, was lagging far behind the three Ladakhi men. When he signaled for them to stop and return to camp, they either did not see him or ignored him. Watching as they pushed on, the frostbitten Harbhajan Singh had no choice but to descend back to Camp VI without them.

“When we lost these three people, I was the fourth, I was with them,” he says, gazing beyond me. “I’m in front of you today, but if I would have tried, I would be gone. It’s only God’s gift that I am alive.”

Summit fever, he suspects, had overtaken his men.

At last, at 15:00 that afternoon, an anxious Singh, awaiting news from Advanced Base Camp, heard his walkie-talkie sputter to life. It was Smanla. He had called to inform that they are heading towards the summit.

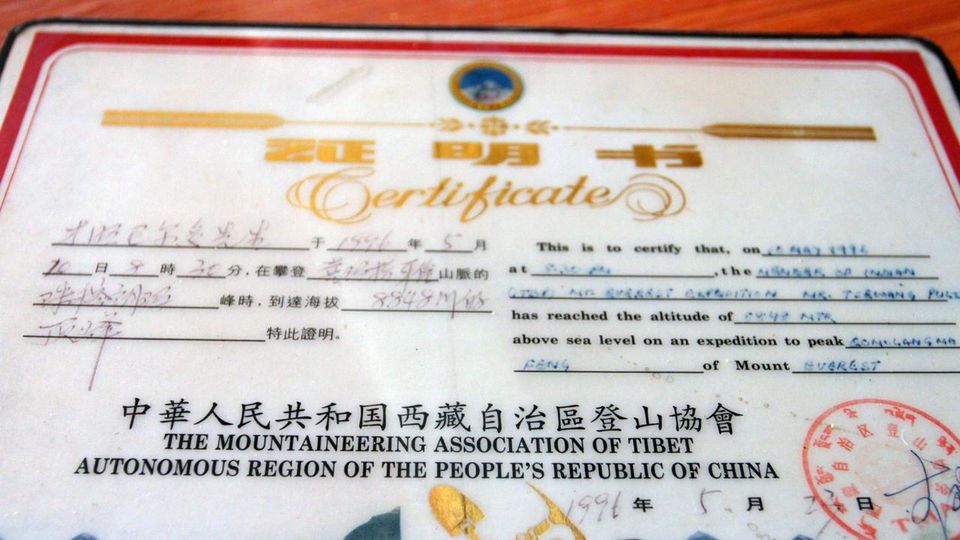

It wasn’t until 17:35 that Singh heard back from his men. A flood of relief and excitement washed over him as Smanla announced that he, Paljor and Morup were standing on the summit. Even as Singh stressed the importance of returning as soon as possible, he began looking forward to the triumphant message that he would send to New Delhi announcing his team’s victory.

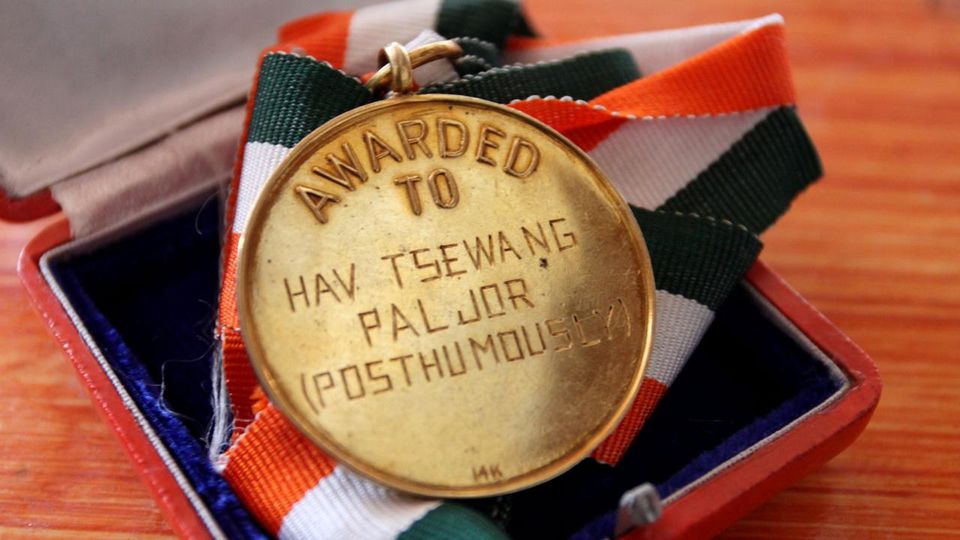

Celebrations immediately ensued, both at home and at camp. The men had just set a record for their country. Whether Paljor and his teammates actually summited, however, was later called into question. Krakauer and others suspect that the men unintentionally stopped 150m (500ft) short of the peak, believing – due to increasingly bad weather and the mental haze of high altitude – that they had reached the top. Despite the uncertainty, however, they are credited with the ascent, as the trophies Tashi Angmo later received on behalf of her dead son attest. As Singh says: “They made it, they accepted that they made it, and I confirmed it.”

Yet the jubilant feeling at camp was to be short-lived. Shortly after Smanla called, the weather, which had been steadily deteriorating, broke. The infamous 1996 blizzard had arrived, cloaking the mountain in a fury of snow and wind. Trying to keep his fears at bay, Singh told himself that the men would be fine, that they had dealt with worst weather in the past. If they hustled, they could even make it back to Camp VI by midnight. “However,” he later recalled, “this did not happen.”

By 20:00 on the night of Smanla, Paljor and Morup’s ascent, Singh could no longer contain his worry. He decided to approach a Japanese commercial climbing team from Fukuoka for help. Two of the team’s climbers, Hiroshi Hanada and Eisuke Shigekawa, planned to leave for the summit that night.

It was told that both of them never helped Smanla and Paljor and left them dying.

As with so much that happens on Everest, the events of that May day in 1996 are no doubt clouded by subjectivity, self-interest and the mind-clouding effects of high altitude, and we will likely never really know what transpired in the last hours of Paljor, Smanla and Morup’s lives.

Though Paljor died a hero, his family received pittance while his body would remain on the mountain, becoming a morbid fixture of the landscape. When Everest takes a life, it also keeps it. Eventually, he became Green Boots – a climber without a name that people would pass by every year en-route to their own personal glory.