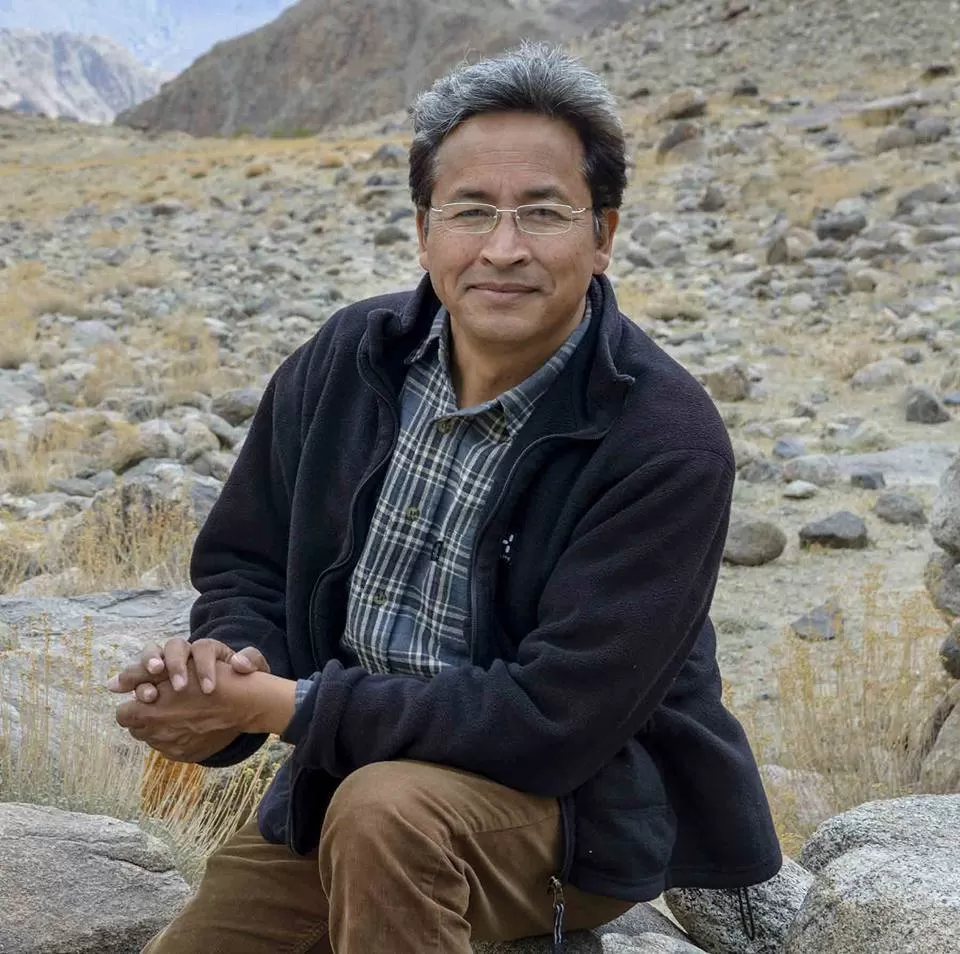

I chanced upon meeting Mr. Sonam Wangchuk first, while I was working with a Buddhist lineage in Ladakh back in 2013. It was during one of those media trips I organised, when a journalist insisted on meeting him and me as a dutiful PR accompanied her for an interview. Mr. Wangchuk is the face behind building artificial Ice stupas in Ladakh and I will admit that I was simply impressed with the vision he hold. I wasn't a writer then, not even in my distant dream else writing on him would be a pleasure

Time went by and I forgot about it completely. I got busy with traveling but it was only recently that I was reminded of him again during a chance conversation with a friend. That's when my mind tickled and ever since there was an urge within me that I could meet him and interview personally.

As the forces had it, I flew to Ladakh in July on an invitation from ScoutMyTrip and OyoRooms to attend the Highest Bloggers Meet.

And the first thing I did was picking up the phone and seeking his appointment. I was lucky for two reasons. First I was flying to Leh, while the rest of the team was joining us a day later and second that he was available for the interview. It was a dream come true to meet this man. Want to know about him. Continue reading ????

Mr. Wangchuk is a mechanical engineer by profession and the founder director of Students' Educational and Cultural Movement of Ladakh (SECMOL) which was formed by a group of students in 1988 with an aim of transforming the education system for younger Ladakhi generation.

Wangchuk with his efforts have kept SECMOL environment friendly which runs entirely on solar energy and uses no fossil fuels for cooking, lighting or heating. The school's students even designed solar-powered mud houses uniquely adapted to the region's climatic conditions. Infact when I met him, he invited me to join the 12 day Sun and Earth Festival which he organised in Phyang village of Ladakh. SEF mainly focused upon learning the essentials of building using earth and solar energy with experts from around the world. But I couldn't him since I joined the SMT team for the remaining road trip

He is said to be the inspiration for Aamir Khan's character in 3 Idiots. Remember those innovative ideas? Though he loves denying it but the fact that Mr. Sonam Wangchuk became the only second Indian to win the much coveted Rolex Award for his contribution to make this world a better place, makes it all say.

Life in Ladakh

Climate change globally has impacted the environment drastically but in an ecologically fragile zone like Ladakh, it is more discern able. Global warming threatens ice shelves everywhere and researchers believe that Himalayan glaciers are shrinking quicker than any other on earth.

Life in Ladakh has always been tough. Braving the dry and harsh weather, 80 percent of Ladakh population depends on farming which requires adequate water. Being a rain deficient area, Ladakh receives an average 50mm of rainfall each year, thus making people dependent on the glacier water which melts during the month of June. The problem is the farmers face extreme water shortage during the crucial sowing season between March and May, from this source

Some of the adjoining villages traditionally followed a system wherein the first village which falls in the line of the streams flowing down from the mountain, would irrigate all its fields. After which they would release the remaining water to the other village which is at a lower altitude. As a result, the down height villages would face water shortage and took to drip irrigation.

Introducing Ice Stupas in Ladakh

During the extreme winters, titanic shelves of the ice form at high altitudes mountains and melt throughout the spring, flowing downwards into the streams that are the only source of civilisation on the mountain. Lately, the cycle has sadly faltered.

"The only reason people can live in Ladakh is the glaciers. Ladakh livelihood majorly depends on farming and the water shortage is only adding to the woes" Wangchuk says

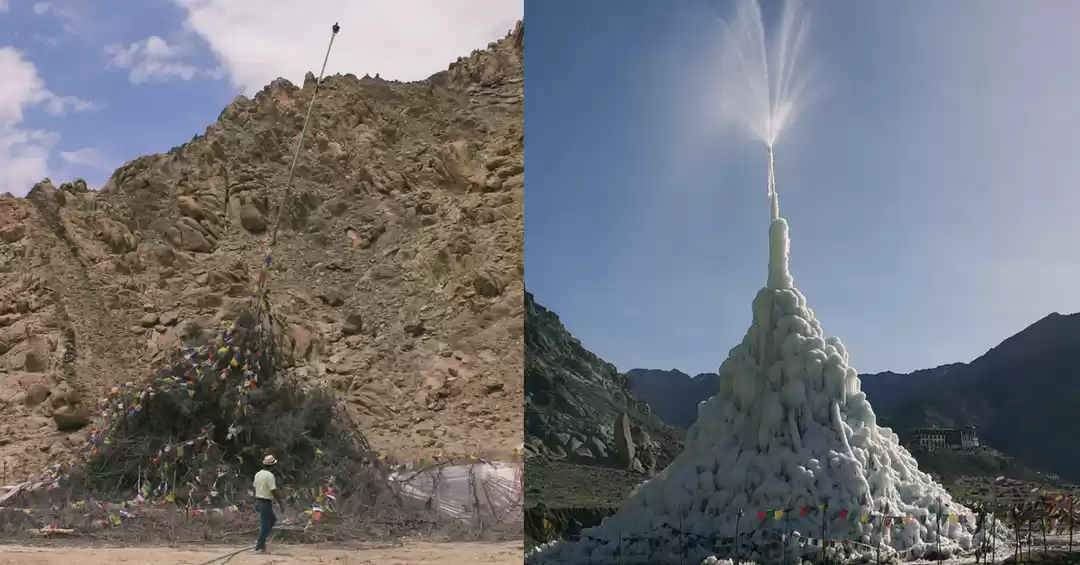

Addressing the increasing need of water shortage in Ladakh, Sonam Wangchuk introduced artificial Ice Stupas - a cone shaped structure to store water which has resembleance to buddhist stupas, much to the liking of the locals

The idea didn't stick him until he saw the chunk of ice: still hanging, improbably, beneath the bridge, long after the shards around it had melted.

In that moment, he says, "I understood that it was not the warmth of the sun that was melting the ice. It was the direct sunlight."

What Wangchuck saw that day was realised four years ago, when he unveiled his first "ice stupa" and for which in December he received a prestigious £80,000 innovation prize by Rolex. " I will use this money to create the next generation of ice towers" he said. Approximately 20 more, each 100 feet high, are in the works.

Traditional Practices

Wangchuk is not the first to try to wring a more sustainable water supply from the mountains. For centuries, inhabitants of the Hindu Kush and Karakoram ranges have practiced "Glacier Grafting",chipping away at existing ice and pooling the pieces at higher altitudes, hoping to create new glaciers that can supply streams throughout the growing season. Apocryphally, villagers in the 13th century build such glaciers across mountain passes to stop the advance of Genghis Khan.

About a decade ago, another engineer from Ladakh Mr. Chewang Norphel, who earned the nickname of "iceman of Ladakh", built artificial glaciers to help solve the problem of water shortage in Ladakh. I wanted to meet him too but couldn't get his appointment (maybe due to old age).

He used network of pipes to divert melt water into artificial lakes on shaded sides of the mountain. The water would freeze at night, creating glaciers that grew each day as new water flowed into the basin. Norphel created 11 reservoirs that supplied water to 10,000 people. But these glaciers had limitation ...

Norphel's glaciers being flat, with a large surface area, melted too fast.

Mr. Norphel work to an extend, inspired Wangchuk to start afresh.

"The problem was that it couldn't be done in lower altitudes, where people actually live," says Wangchuk. He explained further "I saw the problems that the people were facing. The artificial glaciers were built at a very high altitude and villagers were reluctant to climb so high. I wondered why we couldn't construct glaciers right there in the village. The temperature is low enough to keep the water frozen - we just needed a smart way to make these glaciers,"

In 2014, Wangchuk, with a team of SECMOL students constructed a prototype on the banks of Indus River at an altitude of 10,400 feet - the warmest possible location and the lowest possible altitude. If it could work here, it could work anywhere.

Wangchuk hit upon the idea of constructing vertical cones of ice to reduce surface area, slow down the melting and make the water last longer.

"The ice needed to be shaded - but how?" he says. "We couldn't have it under a bridge, or use reflectors, which aren't practical at scale. So we thought of this conical shape: making ice shade itself."

The conical shape hit a sweet spot, maximising the volume of ice which can grow, while minimising the surface area exposed to direct sunlight, which means it keeps melting well into the spring, releasing up to 50,000 litres of water each day by "storing it in the sky", Wangchuk says.

"We faced many problems during the operation. The pipes would freeze, the quality of which was sub-standard. The situation was salvaged when Jain Irrigation stepped in to quickly supply good quality pipes". "No electricity has been used to pump the water to a higher level. The structure relies on the principles of 'water finding its own level'." He said

Long pipes dug six feet deep brought water from an upstream river during the winter months to the site. The water gushing out from the ground through a pipe to reach the tip worked on gravitational pressure. The water would freeze instantly in sub-zero temperature of Ladakh! A conical scaffolding gave the glacier its shape that gradually reached a height of 64 feet. It broke the Guinness' Book of World Records of the biggest man-made ice structure.

Word spread quickly drawing curiosity, interest and support. His Holiness Drikung Kyabgon Chetsang Rinpochey, the head of Phyang monastery with an abiding concern for the environment, saw its great promise.

"Because it resembles something we have in our tradition, it is made more close to the population, to their hearts," he says.

The simple idea of these men has received acclaim across the globe clearly indicating that if man is the one responsible for disturbing nature, he has the capacity to save it as well

Reproducing Content & photographs from this website is prohibited without Author's approval and liable for strict action

This blog was originally published on Buoyant Feet.