“My back has burnt with the heat,” says Bajrang Goswami, sitting on the ground in the sparse shade of a clutch of khejri trees, just outside Gajuvas village. “The heat is up, the harvest is down,” he adds, glancing at the dunes of reaped bajra. A lone camel stands nearby, munching dry grass on the 22 bighas of land he and his wife Raj Kaur cultivate as sharecroppers in Taranagar tehsil of Rajasthan’s Churu district.

“The sun is hot on the head, the sand is hot on the feet,” says Geeta Devi Nayak of Sujangarh tehsil, south of Taranagar. A landless widow, Geeta Devi labours on farmland owned by Bhagwani Devi Choudhary’s family. The two have just completed work for the day around 5 p.m. in Gudawari village. “Garmi hee garmi pade aaj kal [It’s heat and more heat nowadays] ,” says Bhagwani Devi.

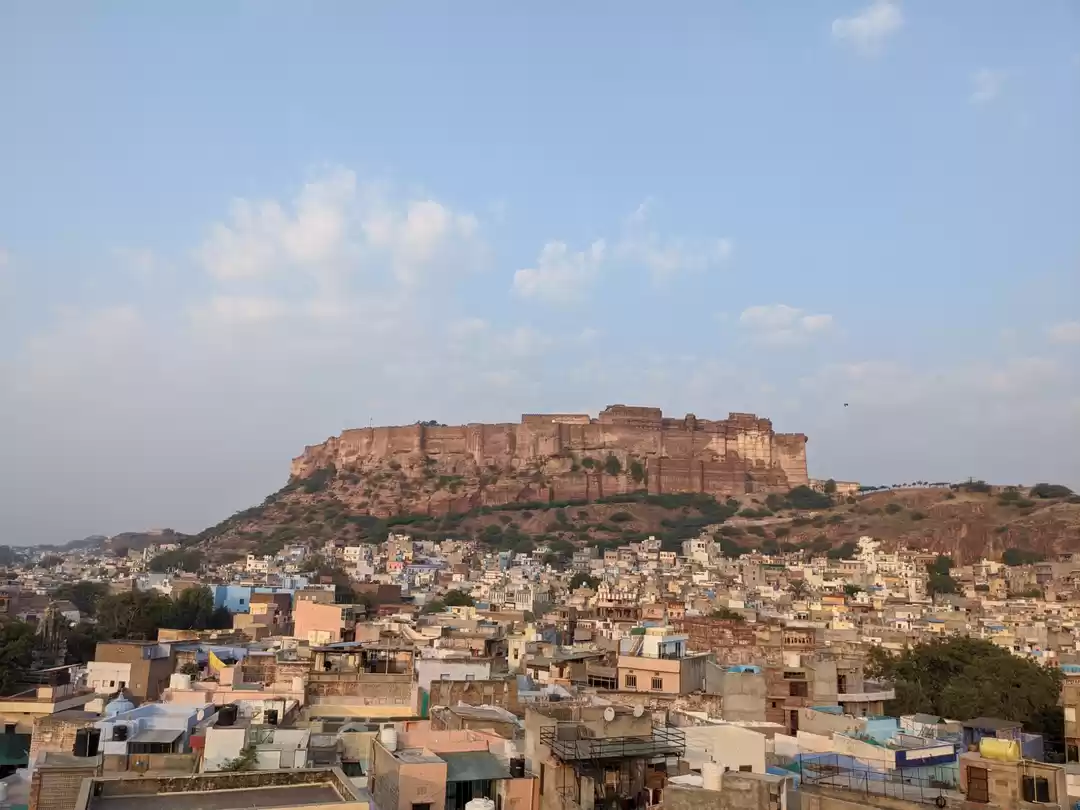

In Churu district of north Rajasthan, where the sandy ground sizzles in the summers and the wind feels like a furnace in May and June, conversations about the heat – and how it is intensifying – are common. Temperatures in those months easily climb up to the high 40s. Just last month, May 2020, the temperature rose to 50 degree Celsius – and was the highest in the world, news reports said, for May 26.

So last year, when the mercury breached even the 51 degrees Celsius mark in Churu in early June 2019 – more than halfway to the boiling point of water – for many it was a sidebar. “I recall it reached 50 degrees around 30 years ago too,” says 75-year-old Hardayalji Singh, a retired schoolteacher and landowner, reclining on a cot in his large house in Gajuvas village.

Six months later, by December-January in some years, Churu has seen just-below zero degrees temperatures. And in February 2020, the India Meteorological Department found the lowest minimum temperature in the plains of India to be in Churu, at 4.1 degrees.

Across this wide temperature arc – from minus 1 to 51 degrees Celsius – it’s the hotter end that people in the district speak more about. Not the dramatic 50-plus degrees of June 2019 or the 50 degrees of last month, but of a prolonged summer that’s engulfing the other seasons.

“In the past that [blazing heat] would last for a day or two,” says Prof. H. R. Isran, a resident of Churu town and former principal of the S. K. Government College in nearby Sikar district, who many regard as a mentor. “Now such heat extends for many days. The entire summer has expanded.”

In June 2019, recalls Amrita Choudhary, “We could not walk on the road at mid-day, our chappals would stick to the tar.” Still, like the others, Choudhary, who runs Disha Shekhawati, an organisation in Sujangarh town that produces tie-and-dye garments, is more concerned about the deepening of the summer. “Even in this hot region, the heat is increasing as well as starting earlier,” she says.

“The summer has extended by one-and-a-half months,” estimates Bhagwani Devi in Gudawari village. Like her, many in the villages of Churu district speak of how the seasons have shifted – the spreading summer has eaten into the winter weeks after compressing the monsoon months in between – and how the 12 calendar months have got mixed up.

It is these creeping changes in the climate – not that single week of 51 degrees Celsius or a few days of 50 degrees last month – that has them worried.