“Do you need a guide?” A small voice asked. I looked down and saw a small boy clad in a blue shirt and dark pants. He named a price.

“How old are you?” I asked incredulous.

He drew himself up to his full height and announced proudly, “I’m eight years old.”

I had mixed feelings. I was wary of using child labour, but I was intrigued too. No doubt his family needed the money – that’s why he was here. I conferred in Tamil with my friend Lakshmi and we decided to say yes. For obvious reasons we didn’t negotiate.

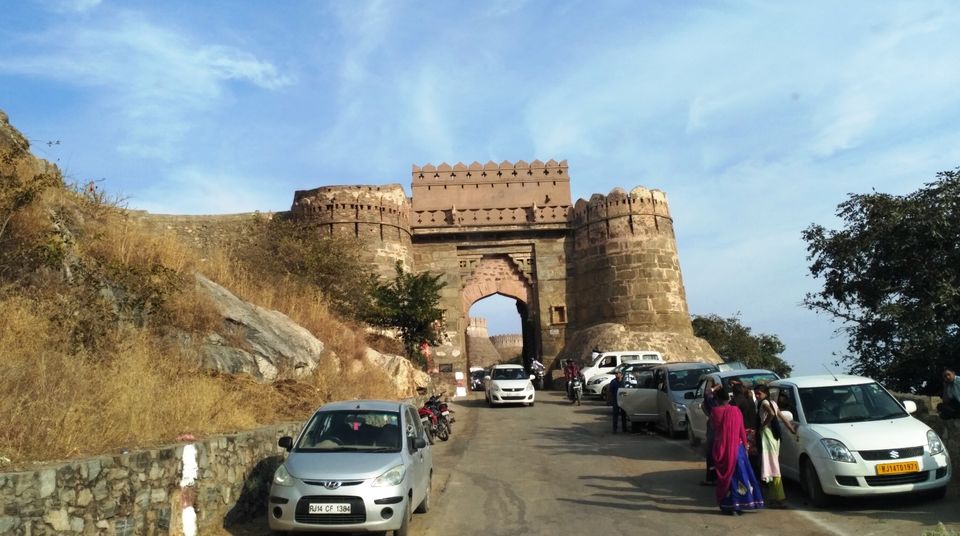

We were at the entrance to the Kumbhalgarh Fort, that imposing structure they sometimes call the Great Wall of India. It was late in the afternoon and thankfully the sun was nowhere in sight. Our climb would be that much easier. Later that night there would be a full moon. We soon noticed there were many child guides swarming over the place. So our boy wasn’t the only one.

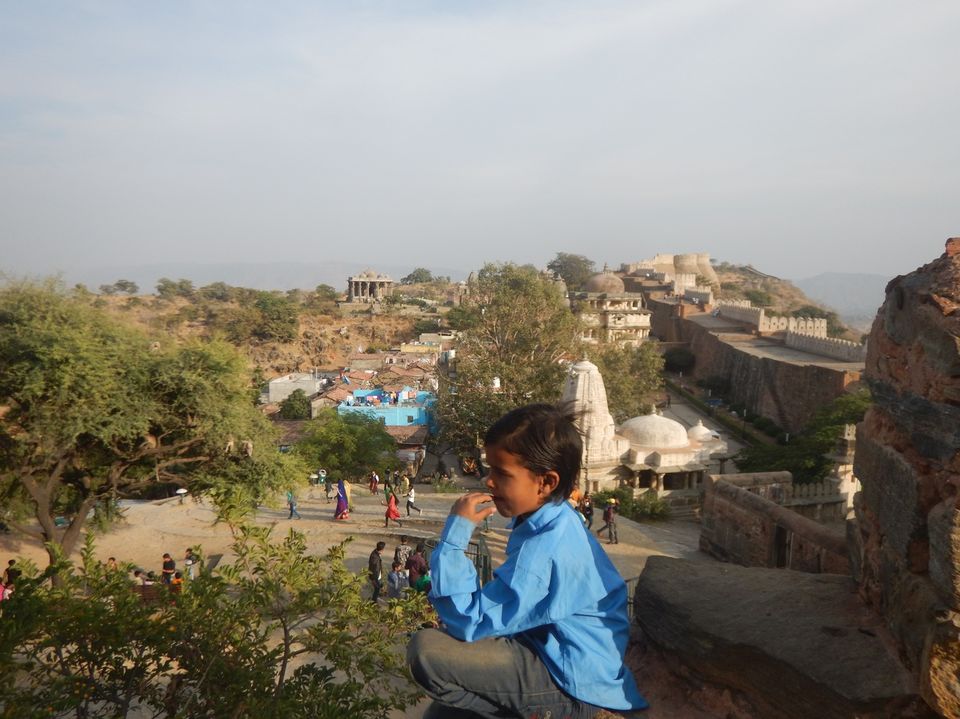

“I’m not allowed to go all the way to the top,” the boy explained. “You see that palm tree over there?” He pointed to a tree half way up the fort. “I’ll take you up to that point. But don’t worry, I’ll tell you where to go and what to see.” Seeing our perplexed looks he elaborated, “Because I’m small, you see, I don’t have permission to go to the top.” We smiled, said ok and followed him.

There was a spring in his step. We found it hard to catch up. When Lakshmi lagged behind, he told me “Ask her to come fast!” I said with a smile, “My child, we are old people, we can’t walk fast.”

He sat down on a rock, waited for Lakshmi to catch up and began his narrative. He was as good as any ASI certified guide, rambling off historical facts and architectural funda at breakneck speed. Hindi isn’t exactly my strong point, but I’d done my share of research so I could understand what he was saying. And yes, he made no mistake. His knowledge was faultless, his confidence and enthusiasm were mind-boggling. Someday, this guy is going to be somebody, I thought to myself.

“Give me your camera. Go stand over there. I’ll take your picture.” I handed over my camera and tried to tell him what to do. “I’m an expert,” he said coolly. After taking the picture he asked, “Can I keep the camera around my neck?” I was really touched, but I had to say no. “Then how will I take pictures?” I asked him. He understood, but he must have been disappointed.

Rana Kumbha had built the 36 kilometre wall on the banks of the Banas River, covering 13 mountain peaks of the western Aravalli Range sometime in the 15th century. There are 7 gates, the main gate being called Ram Pol. Our boy guide rattled off all the names in quick succession: Hanuman Pol, ......He did not mention the human sacrifice but I had read about it. For the success of the venture and to propitiate the gods a holy man was sacrificed and a temple built where his head fell. The story goes that he volunteered, but who knows? Those were the days.

Kumbhalgarh is the second largest fort in Rajasthan, after the legendary Chittorgarh. There is an impressive sound and light show in the evenings but we missed it because it was cancelled on the day of our visit to accommodate some cultural program.

No one can deny that Kumbhalgarh is a work of stupendous proportions. Everything about it is magnificent - the bulbous protrusions, the battlements, the lookout towers, and the solid masonry. They say eight horses could ride abreast atop the battlements.

Mewar, in the Rajputana region, apparently has 84 forts, of which no less than 32 were built by Rana Kumbha during his 35 year reign. He had extended his kingdom from Ranthambore to Gwalior, and how! Incidentally, the 9 storey Vijaya Stambh at Chittorgarh was built by Rana Kumbha too. And his birth name was Kumbhakarna! The forts are living proof that the man slept very little, unlike his legendary namesake. The Ranakpur Trailokya-dipaka Jain temple was his handiwork too.

It was in Kumbhalgarh that Udai Sigh II (founder of Udaipur) took refuge after the supreme sacrifice of his wet nurse Panna Dhai, who allowed her son Chandan to be killed instead of the prince. His mother Rani Karnavati had committed jauhar on 8th March 1535 following the defeat of Chittorgarh at the hands of Sultan Bhadur Shah of Gujarat. She had ruled for 6 years as regent. Earlier her husband Rana Sangha had unsuccessfully led a Rajput confederation against Babur in 1527 and died of wounds sustained in battle. Those were troubled times. Udai Singh’s cousin usurped the throne, killed his elder brother Vikramaditya and would have killed him too, but for Panna Dhai’s timely intervention. In Kumbhalgarh he lived incognito for two years before being crowned by the nobles of Mewar. His son Maharana Pratap was born in here in 1540. A steep flight of stairs led to the room. We were reluctant to go up. We asked some boys who were coming down the steps, and they told us the room was closed.

The Badal Mahal is right at the top. The King’s and Queen’s quarters are pretty humble as they come.

There are dozens of temples within the fortifications. Near the Ram Pol you find the Neelkanth Mahadev temple with a king-sized shivaling made of black stone. They claim it is the biggest in the world, but that’s not true. A hooded serpent stands above the shivaling and by the side is placed a trident, which is obviously a recent addition. The temple was built in 1458.

The Vedi Temple, a three storied structure, also built by Rana Kumbha, was once a sacrificial temple. Ran Kumbha built the Mamadev Temple in 1460. The maintenance of these temples leaves much to be desired. The fort is well maintained though. The only messy part is the stepwell which is tucked away in a corner, out of sight of the tourists. I managed to get a peek and a picture.

Perhaps the royal women used to bathe here once upon a time. Will the authorities please clean it up? It will certainly add to the glamour of the fort. (I hate to share the picture but I'm pretty sure if I don't it's going to lie that way for the next 100 years.)

Before saying goodbye to the boy guide at the palm tree we asked him his name. He said Annapurna. "But Annapurna is a girl’s name!” I remarked. He was silent. We asked him how many brother and sisters he had. He said four brothers and one sister. We asked him to name his siblings. All the boys had distinctly male names – only Annapurna’s name was effeminate! We did the math and probed further, and finally he admitted he’s a girl. I wondered how many of the other child guides we had encountered that day were girls too. There were certainly none dressed in female attire.

We had learnt a valuable lesson in sociology. To ponder over the implications we had plenty of time. This was our own ‘incredible India’.