Thirty homo sapiens on ten gypsies stand still without making a sound. It’s afternoon but there’s a nip in the air that makes them shiver. Nothing penetrates the deafening silence. Their gazes are fixed at a wall of green - an entangled mess of grass, trees and shrubs. Eyes flit from one face to other, each as attentive and clueless as before. A bark pierces the air and refuses to stop. It’s not coming from the throat of a dog, that much is evident. Like an instrument in an A.R Rahman composition, a growl enters the as yet singular orchestra and continues to play on loop. There are no highs and lows to any of this mechanical consistency for fifteen minutes until the bark ends in a long, all consuming scream. This is the cue for the end of the show. In a second the audience is gone, speeding away in a wake of dust and heavy Tyre trails on mud.

The tiger has made its kill.

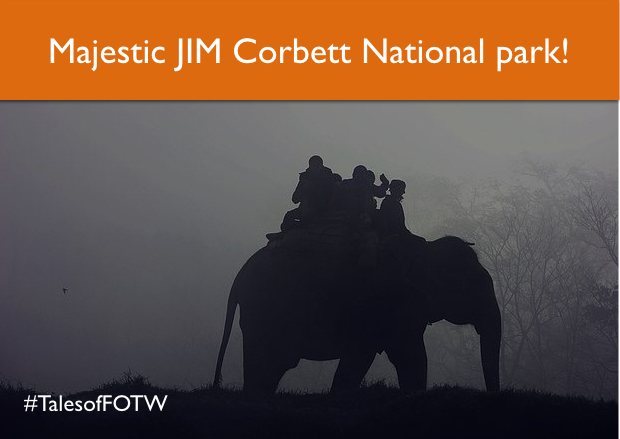

I have grown up watching hours of Nat Geo and Discovery (gotten quite adept at the latter’s shuddh hindi and often dramatic style of narration) on TV and nothing beats the opportunity to experience all of that - not sitting with an option to switch channels during advertisements but in an open jeep with one of your closest friends, right there in the middle of all action. Ever since that unfortunate white tiger attacked that unfortunate young man at the Delhi Zoo, I have only wanted more to act on my impulse to go into the wild. Circumstances found me in Delhi at just the right time too; the most rewarding forest zone to visit opened exactly a week before the night I took a train from the nation’s capital to the sleepy Ramnagar, the closest railhead to Corbett National Park. Alighting from the train on a chilly winter morning to find a dozen or so gypsies waiting for travellers at the station is truly a sight, or so I imagined later. To chashma-less and contact lens-less me, most happenings of this strange, sleepy place were being relayed through my ears. I remember hearing a surge of people pouring out onto the road at 5 am, the frenzied calls of drivers who knew who they were supposed to receive and the whooshing sound of the cars as they sped away, just in time for the morning safari. And then, silence. So profound that coupled with the cold, I almost lost the will to speak for a while. (Also note that I was helplessly struggling all this while to restore my eyesight in the waiting room.)

Lens fits. Time to go.

Fast forward to 10 am. By this time we have found a driver who’ll be responsible for our safaris, we have gorged on chai, maggi and dip-dip biscuits, processed the permits required to stay the night in the jungle, listened to late 90s and early 2000s’ Good Male Singer-Alka Yagnik hits blaring from our jeep (a little embarrassingly at first, I admit) and landed ourselves at Gairal, our rest house. When the safari begins, my expectations are going interstellar. I day dream of pugmarks and blood stains, of a crouching tiger and unaware deer, of frantic wild monkey calls from the top of trees, of a python lazily dangling from a branch, of an eagle swooping in and ripping apart a fish. I want blood, I want gore. I have purchased the ticket to an action movie (a wrestling match!) and I want value for every rupee spent. Why should I settle for anything less? Isn’t that what predators do in the wild – grab their prey by the neck after playing hide-and-seek with them? There’s confrontation. There’s deceit. There’s innocence lost. There’s grandeur. There’s primal fear. Plainly put, the jungle is a Shakespearean tragedy. Why then does it escape me? Am I not good enough for this place? Why is all I see heaps and heaps of elephant shit and anthills? Something is missing.

That something would be an inability to look at the jungle as their home. Think about it. Do we sing for every person who rings the doorbell? Do I rush to write a blog post about everyone who’s approaching me? Do I dance around so that my parents can spot me? At home, we just be. And that’s what they were doing, just be-ing in their habitat. Indifferent to this city boy who’d come to see them ‘perform’.

Once I learnt this lesson, I realised I had a new pair of eyes. I don’t know if it is just Corbett or this is how the wild anywhere is, but the place I am talking about was definitely a notch higher than the ‘natural’ beauty I had seen until then. There were dense forests on either side of our winding and climbing road in the beginning which would give way to a dried-up riverbed once in a while, then on to open forests with sunlight weaving magic from between the foliage and finally to the grasslands next to a huge reservoir lake with mist hanging on golden grass, like blessings on a wheat field. The grasslands are special because they are ideal tiger spotting places. You can make out that a tiger is on the move if you see freshly trampled grass. Come February and it will be all gone; the forest officials set fire to this whole place to make way for new grass to spring up. That is not the only thing that changes about the grasslands. Parts of the grasslands get submerged from time to time as the water levels increase in the Ramganga reservoir, shutting off trails in an ever-changing landscape.

All roads lead to that one creation of God, perhaps God himself as far as this pilgrimage is concerned and that is of course the Royal Bengal Tiger. I sighted a young one for less than a minute before it disappeared into the bushes and wasn’t as lucky the rest of the time (thanks to an indifferent driver who inexplicably harboured a silent grudge against us), the dramatic face-off between the tiger and a barking deer I described in the first paragraph being an auditory highlight of the entire trip. The pictures I saw on the cameras of the fortunate ones left me with a deep sense of awe for the tiger and everyone in the jungle. As a natural selection of my own being, I always gravitate towards a sense of loss and hardship, and I could distinctly feel how trying and different life in the wild is. You live in constant fear of being hunted. You can’t speak up. You don’t know much and you are often left at the mercy of humans. You are feared but seldom loved. You have no home to come back to every day. Left alone, you most certainly will perish.

My last memory of the place is looking at the stuffed skin of a man-eater tiger in the small Jim Corbett museum. In keeping with how most of us think of this beast, the tiger is shown with his mouth open, baring deadly fangs. One would think he might have been roaring when he died. I try to imagine its last moments as it died of pneumonia. Was it aware of his crime, or even the concept of ‘crime’? Did it also wonder about life the way we do, looking back on its past? Do animals have regrets, remember their first love, have insecurities about the way they look and are, get hurt if someone is not nice to them, and worry about how in a few years there might not be any of their species left?

I think not, but then have we ever understood them completely? I think not.