Aru kiman dur? (How much more?)

I turned around and saw my friends struggling to climb up the hill. One had already removed his jacket and tied it around his waist. We were on our way to the India-Burma (now Myanmar) border that was on top of a hill. While we waited in silence, a slight breeze hit my face and I heard the chirping of a bird not so far away. Though the sun was directly overhead, in the middle of the afternoon, the breeze made me forget the heat for a while. I turned around and saw our guide aimlessly looking around waiting for us to resume our trail.

Let’s go guys! And I started walking again.

How come you’re not already tired? One of my friends asked.

My stamina is better than you two, I said with a mocking smile. Now let’s go!

After some more huffing and puffing, we finally reached the top. I excitedly looked around but all I saw was barren land on one side and big bushes on the other. My friends and I exchanged confused look. Our guide was already on his way towards an abandoned wooden gate, which was hardly seen amidst the bushes. He started climbing up the stairs beyond the gate. We followed him and reached a small clearing on the far top where there was one big stone in the middle. On the stone was carved India on one side and Burma on the side. We were finally there.

Covered with hills from all sides, this place was Longwa’s gemstone. I looked down at the village, which appeared as tiny monopoly board game houses that were scattered around the area. This village ran across the border and the chief’s house fell right in the middle of it. The villagers did not need a visa to move around freely to Myanmar. One village, two nations.

We stood there absorbing the moment. I looked up and whispered a tiny prayer thanking Mother Nature for such a sight. I could sense everyone standing still and breathing in the scenery while the gentle breeze calmed out heart rates and erased our sweat beads.

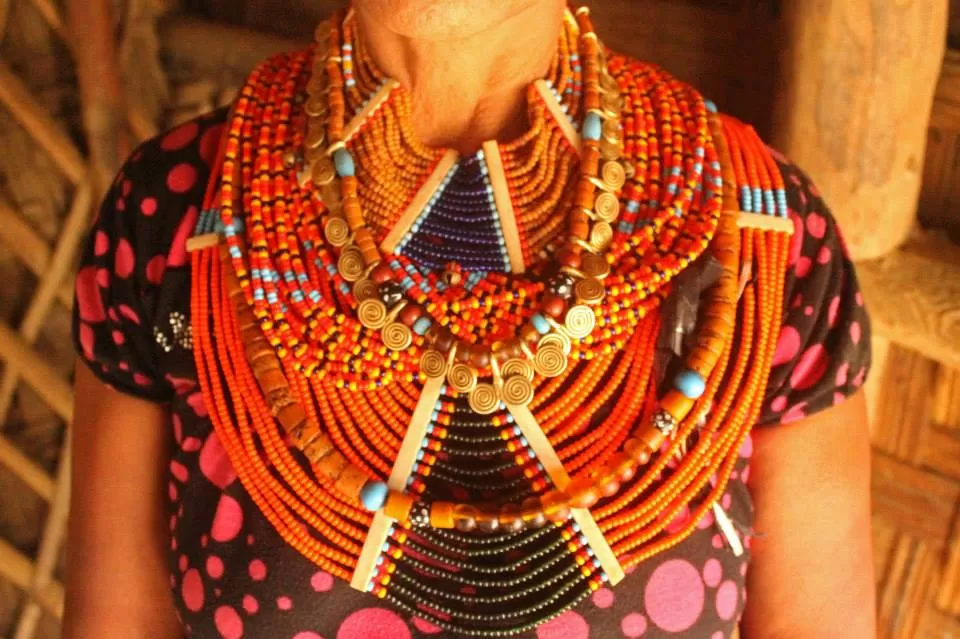

My thoughts took me back to a week before when three friends decided to take a trip to Longwa, the largest village in Mon district, which lies in the northernmost part of the Nagaland state in North East India. The tribe that largely inhabits this area is the Konyak Tribe, who has dual citizenship. This tribe is very famous for their violent head hunting with their tattooed inked faces. The warrior with the maximum numbers of his enemies’ heads is considered to be the mightiest of all. They always wear some traditional jewellery and most of the men with inked face wore a brass skull necklace, which denoted the number of heads taken by them. Killing and severing an enemy’s head was considered a rite of passage for young boys, and success was rewarded with a prestigious facial tattoo. The Konyak warrior believed that taking head increases the fertility of the crops as well as the well being of the warrior who took the head.

Excited and a bit apprehensive, as this area is considered as a Naxalite area, we embarked on our journey. After an overnight ride by bus, we reached the Nagaland border. The next leg of the journey was in a shared taxi to Mon district. With no proper roads, it was a super bumpy ride in a crammed taxi. I was stuck in between my friends and an old drunk Naga (people of Nagaland are called Nagas), who somehow squeezed in the same backseat. I even managed to get some sleep while my body swinged from one side to the other at every sharp hairpin bend and jumped whenever we were on a stone graveled road. Once in a while, my head would hit the seat in the front. I would wake up to hear my friend having a bizarre conversation with the old fellow. Both of them were speaking in broken Hindi and were having a great time talking about a peacock that the old fellow ate in Delhi and was jailed for a while. I tried hard to listen to this intriguing conversation, but my sleep got the better of me. We reached Mon in the evening and from there took another taxi to reach Longwa. The driver happily spoke about the unnatural incidences that happened in the jungle we were passing, while I was taking names of all the Gods I knew.

Finally we reached Longwa at around 8. The sound of wind welcomed us when the driver killed the engine. I pulled my coat closer and jumped out of the car. It was pitch dark and barren, except the big wooden and thatch house nearby. We followed our host with the help of the little strand of moonlight that shone bright on us. As we entered, I saw in one corner a bunch of men sitting around a fire and smoking opium. The walls of the hut were adorned with skulls and bones of buffaloes, deer, boars, hornbills – prizes from years of hunting. We went further inside to the kitchen where a large fire was burning in the center. Hurriedly we sat around it and started warming out hands and feet. After eating a simple meal, we retired for the night.

That was two days ago. These two days were enough to make me realize that these folks are the most peace loving community that I’ve ever come across. The practice of headhunting was banned after the arrival of Christian missionaries in 1940s. Konyaks were animists, worshipping elements of nature but by late 20th century, more than 90% had accepted Christianity as their religion. They are still ruled by hereditary chieftains, locally knows as ANGH. The practice of polygamy is prevalent among the ANGHS and the chief of Longwa has 60 wives and many children.

Even though the practice is banned, the older generation made sure that they pass on their knowledge to the next generation. There are community halls in different parts of the village where the older ones share their knowledge to the younger ones, so that the tradition is maintained even if it is not practiced. When I spoke to the older people, I was amazed to see that they still possess the zest to take a head(if given a chance). Their eyes sparkled and their body language changed when they spoke about the past. I could see the pride and felt the honor in their words.

Longwa is a remote village in a hilly area and so walking was the only option to reach a place. Thankfully I was hitting the gym in those days, so walking up hills was not a difficult task unlike my other two friends who would run out of breath after every fifteen minutes. We visited the village where brass necklaces worn by the headhunters were made. I picked up one with a single head for myself. They even added some traditional beads to make it more glamorous and pretty. Some of the Konyaks are into gun trading business with Myanmar. These guns are mostly used for their own safety, as the area is full of wild animals.

While mornings were spend in envying the villagers while looking at the mist covered hills and exploring the area, evening were spend around the fireplace in the kitchen sipping on black tea, nibbling on home made bread and chit chatting with the family members in broken English, as they weren't very fluent in it. But you don’t really need a language to understand each other, do you?. On one such evening, as I sat in the kitchen, listening to the cracking of the woods in the fire, and cupping my cup to feel the warmth of the tea, I looked up at our host’s mother who was sitting right across me. With rosy cheeks and kind eyes, the contentment on her face was bliss to my eyes. Not only her, but everyone I met in the village were so happy and gay. There is absolutely nothing to do and life was very simple, but still these folks were so warm and self-sufficient. That night, we feast on the most delicious food, and can almost tell that it’s been cooked with ingredients grown there in their backyard; dinner was a cucumber curry and an unknown animal’s meat which was slow cooked with vegetables served with rice. After dinner, as we walked towards our room, I saw the moon casts a haunting glow on the carved old doors which made up our rustic hut, and back in our room, a gentle breeze and the sounds of the night kept us company. When I woke up at midnight to go to the bathroom outside, I heard the wind getting ferocious and coaxed myself back to bed!

Now standing at the border, I felt like time flew away in one glance and today was our last day in Longwa. My heart already felt heavy just thinking about leaving this place. My musings were interrupted by the guide voice:

Let’s go down and meet the chief.

We started ascending down. I particularly had difficulties and I wasn’t wearing proper shoes. They were slippery sneakers and did not suit the region. But my friends supported me whenever I needed help. With some ‘i’m gonna fall’ and ‘come back, I need help ‘cries, we finally reached the village. One peculiar thing that I noticed was that wherever we went, the villagers would come display a range of jewelry and craft items that they’ve made or produced from Myanmar. This time too, it was no different. Out of all the items displayed, one thing that caught our eye was a chimpanzee’s hand that can be used as a back scatter. My friend wanted to buy it but our guide warned us that it is an illegal item. With a longing look on his face, my friend kept it back and we moved on.

At the chief’s house, we were fascinated to learn that the sleeping quarters were on the Myanmar side whereas the kitchen was on the India side. Unfortunately the chief was sleeping during that time and we missed our opportunity to meet him. But fortunately, we were treated to some black tea and bread. Also my friend forgot about the scratter by the sight of food. With a filled belly and satisfied soul, we thanked the chief’s wives and started on our way back to the homestay. By the time we reached our destination, the sun had already started setting down slowly. I sat outside the porch of our hut to cool myself down. A bunch of kids were playing football with a ball, which was made out of plastic bags. Their clothes and faces were soiled with the dust all around. Looking at them, it dawned on me how attached I have gotten to this place. Far away from the city’s hustle bustle, this place was virgin and fresh. I don’t remember when was the last time I breathed such fresh air. Wilding away time doing nothing was something new and I enjoyed just sitting outside here watching time go by. I realised I will miss waking up everyday to an orchestra of birds, a welcome change from the shrill sounds of the alarm clock. I looked up and saw the sun reaching the horizon but that didn’t have any effect on the kids playing. They were still in their own world laughing and taunting each other jokingly if someone missed a kick. Suddenly, I felt a chill in my bones. The wind was gaining momentum and the windy winter evening was on its way. I gathered up my thoughts and went inside to wear something warm.

That night, our host entertained us with some tribal folk songs while stringing on their locally made instruments. My friends even took few drags from the beautifully carved bamboo pipes used for smoking opium. Anyone in this moment could make out that in this quiet village of Longwa, it is a case of oneness – one village, one identity but two nationalities. Konyak people live on two sides of the boundary line but the emotional bonding among them was strong. This merriment went past our usual bedtime but we didn’t care, time just froze for us.

This January, it was three years since that night in Longwa. Surprisingly, I vividly still remember each and every detail. I didn’t take any notes while I was there but the memories are so strongly ingrained in me that it keeps visiting me every now and then. I don’t know when I will go back to this little village again, but I have been recommending it to every soul who wants to travel in North East India. Unknowingly, this place has made its own comfortable space in my heart and refuses to go away, but I am more than happy to let it stay for as long as it wants.

P.S: the unknown animal I ate turned out to be the Indian Giant Squirrel. I’m glad I didn’t know the name then because when I saw the photo, I cringed.

Photo credit : Syamantak Bhutan.