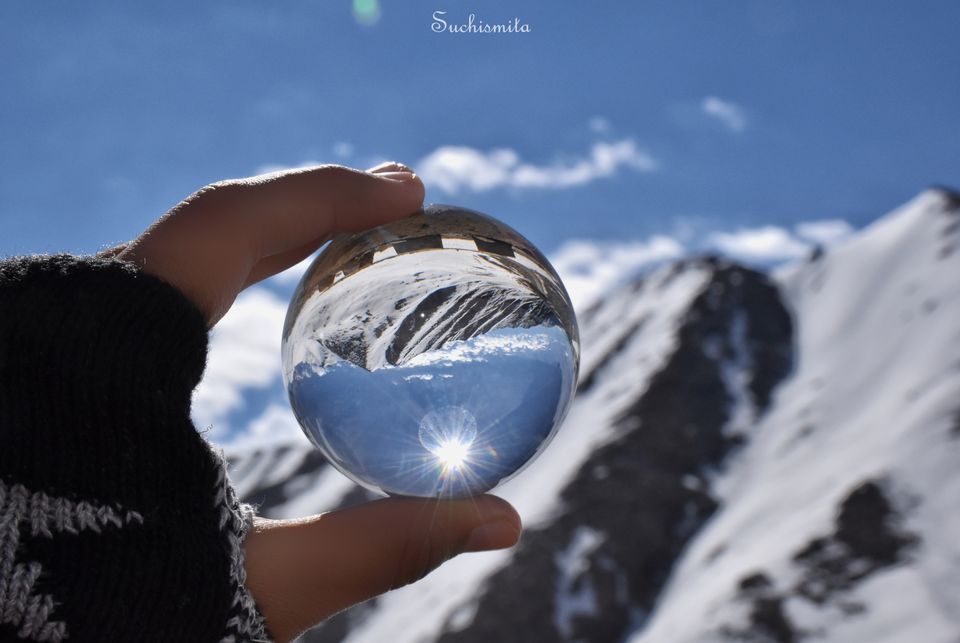

It was 4th July and we woke up at 6 in the morning because it was the world’s highest motorable pass that we had to cross today. Khardung La (“La” means Pass) is the doorway to the Shyok and Nubra valleys, at an altitude of 17,982 feet. It is generally advised at Khardung La to not stay at the top for more than 10 to 15 minutes, or to not run around due to the altitude and lack of oxygen. When I walked into Khardung La at around 8 in the morning and the top was quite uninhabited, the sunlight shimmering over the white snow, the cold waves from the snow walls about to start thawing, I was genuinely excited but at peace at the same time. I was fine, my body had no negative reaction to the altitude, so I stayed a little longer, about 20-25 minutes. I loved the calm and peace I felt deep in my soul and I did run around with my camera in awe. I felt a little proud of myself because when I was small, going on vacations to high altitudes with my family, I remember to have made my parents suffer quite a lot for my health conditions when it came to mountains, but then again I love being in the mountains.

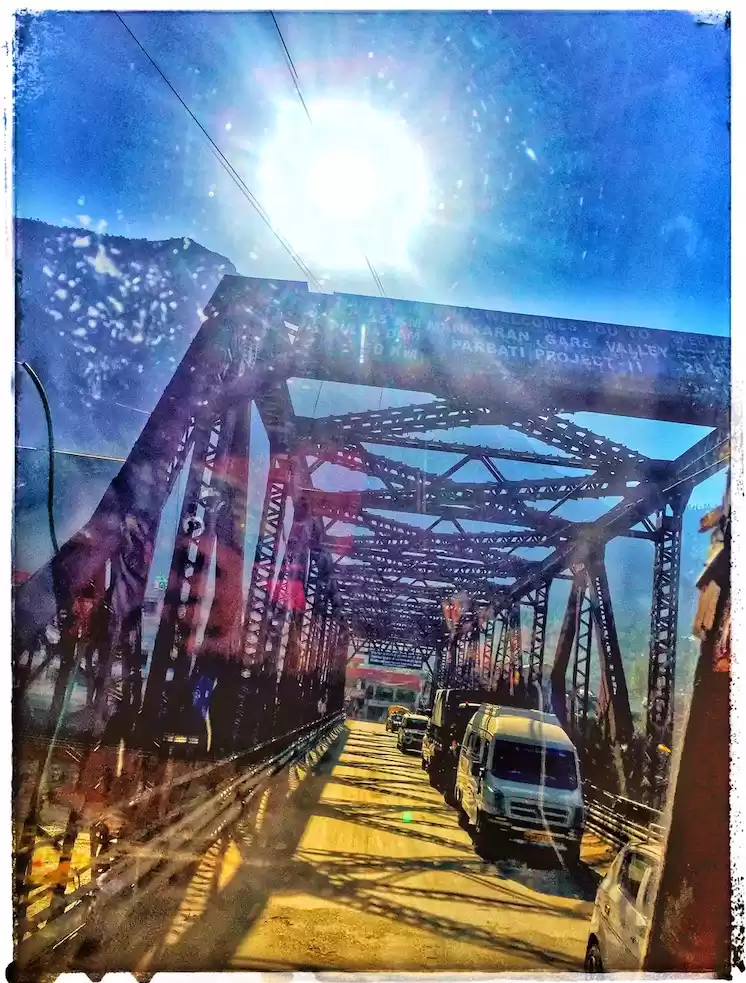

However, a beautifully sunny Khardung La bade us goodbye into the Shyok valley. It was a long drive through dry river beds and I could see small sand dunes starting to form at the foot of the mountains, occasionally a sand twister would appear with the wind. Our plan was to not stop at Diskit or Hunder desert, but to drive to zero point, the India-Pakistan border. Going past Hunder, I could see what a large scale desert it was.

At around 2 pm we reached the border. The Indian Army showed us the metal wire border and bunkers everywhere on the surrounding mountains. The thing is, as much of a place of war tension it might be, it has almost become a hotspot for bikers who’re ready to have a really bumpy ride over boulders and no roads.

By 3 in the afternoon, we had reached Turtuk, and had lunch. Turtuk is a small pretty green village at a far end of Hunder desert. The road to Turtuk seems a little mysterious, more like miles of uninhabited, really steep mountains and stone roads. Turtuk village has an important history. In 1971, the Indian Army took the village within India’s borders after a war with Pakistan. This village, while in Pakistan was under the Baltistan area, so people there speak Balti and Urdu languages. What I saw there and realised was, I saw the only school there that was built by Pakistan’s government, but after 1971 I was happy to see the Indian government didn’t demolish it, it still runs, the same school, built by one country, run by another, sometimes we need these bits of humanity to restore faith in our race! Also, they’ve kept their culture, the Balti language, alive. Turtuk might be a very small, almost insignificant part of India, but they have their own language, their own culture, they haven’t lost it in the sands of time. All these make me think, India is a lot more diverse than what we’re made to read in textbooks and see around us. That’s what urges every traveller to explore in search of more diversity. While we were returning from Turtuk, children were returning home from school, waving at every passing stranger (tourists mostly), gleefully saying something in Balti, rosy cheeks and eyes full of smile.

We reached our Nubra Summer Camp at Hunder by 7:30 in the evening. The sun had started to set and an important point to notice throughout Ladakh is that almost every hotel or guest house or camp or homestay uses solar energy for electricity. This meant, once the sun went down, no more hot water, sometimes frequent powercuts. But well it’s our responsibility to try to use as little water as possible because we’re in a desert after all and our local hosts work hard to bring us all the water they can, same goes for power cuts. We’re almost in the middle of nowhere, so we shouldn’t actually expect to get a polished city-like place to live in. Also, where’s the fun if you are in a desert and not camping without electricity! I find it exciting and even thrilling at times. By 8:30 dinner was done and we retreated to our tents, and the power was out by 9. The darkness that enveloped me then was just pitch black. It was like if I’d stretch my hand out, I wouldn’t be able to see my fingers/palm. It was that dark. I had a wish of staying up to shoot the night sky and stars at around 3 or 4 a.m., but when I woke up I just heard massive gusts of winds almost ready to uproot our tent and rainfall. Yes, rainfall at a desert, and the sky was cloudy.

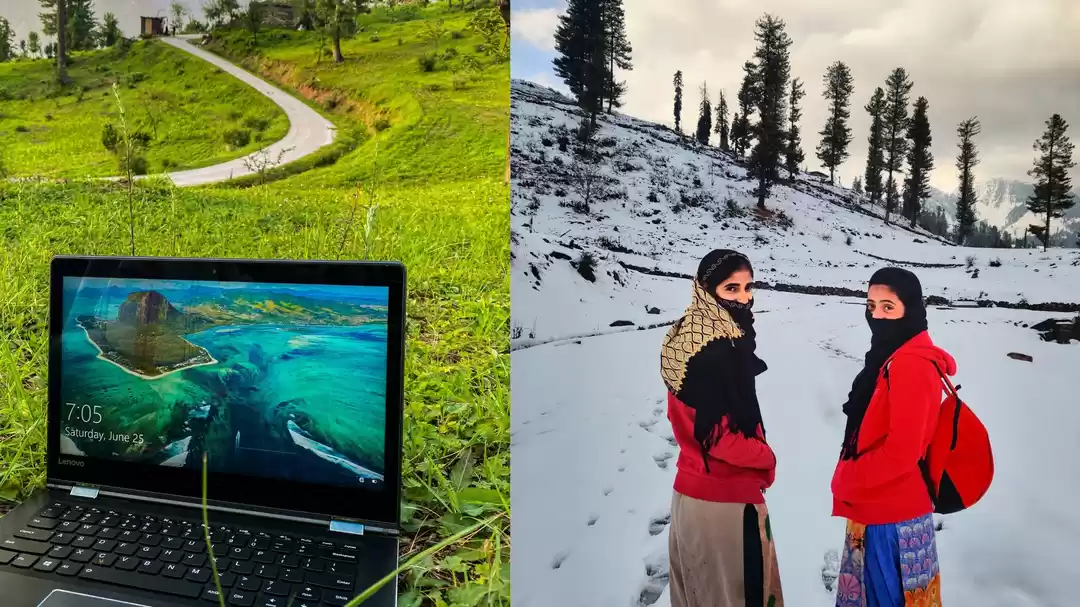

I woke up at 7 a.m., realising that it was still quite cloudy. In a way, the cloudy sky was convenient for me because I wouldn’t want the sun to be blasting it’s rays on my head while I’m at the sand dunes because sand can absorb an enormous amount of heat very fast. It was 5th of July and the first thing I did was to find if there was a stream behind our tent because we could hear water gushing through. Indeed there was a little stream from which our drinking water was channelled into the camp. I was excited about the camel ride until I reached the site of the camels. The thing with camel rides at Nubra was that, it was sad to see these free animals being tagged with numbers and bound in ropes, but again, they get their food depending on how much their owners earn from us, travellers and tourists, so the only way of helping them is, us paying for camel rides. It’s sad but it’s true. Bactrian camels never originated in India, they were originally brought in by the Mughals for trade. Since then they’ve been here in Nubra, once serving for carrying loads during trade, and now as a means of the tourism industry. As I said earlier, this year the annual amount of tourists has decreased in Ladakh by 60% and it’s a worrying factor for all the people whose livelihoods depend on tourism.

So with conflicting thoughts, I did get a camel ride and I won’t disagree, it was fun. There was a time when a camel came up to me and rubbed it’s neck and head on my left leg and went away, and I was terrified because I didn’t know if it was a friendly or unfriendly gesture! And my own camel sneezed on my hand 7 times and maybe I smelt of camel all day, so yeah it was a fun time… then we went to the sand dunes on foot and had a wonderful time rolling around in the sand. It wasn’t too sunny, so the sand was warm and comfortable! I also noticed that the sand here isn’t like the sand on beaches; it’s more like powdered stone, so the colour is also more white-ish.

From the sand dunes we had some black tea at a roadside café and went to the Diskit monastery. It has a 104 feet tall Maitreya Buddha statue seated facing towards Pakistan across the Shyok river valley. The Diskit monastery was built in the 14th century and is another beautiful Ladakhi monastery with intricate details.

From Diskit we left Nubra and headed to Leh, which meant crossing the Khardung La a second time. It was already raining and 4 in the afternoon. We had our lunch at the last stop (Khardung village most probably) before the pass. As we approached Khardung La, we realised snow was coming down with the rain. Soon it turned into a complete snowfall and we reached the Khardung La top. What a sight! A group of bikers were singing in unison out of happiness and last day’s snow covered mountains were even whiter, not leaving a single stone in sight. We again jumped around for sometime in excitement! Our car was covered in snow too. We now had to drive down as soon as possible because the roads were becoming muddier and the air, foggy and blurry. As the car climbed down from the pass, the weather became clearer, and by 6 we were in Leh.

The sun shone brightly and the sky looked clear, but we could see that the darker clouds were still accumulated at the snow peaks where Khardung La was located. Sangaylay Palace welcomed us in Leh once again and we had some warm soup. Khardung La had successfully shown us both of it’s extremities!

P.S.: All the photos here are solely by me.

~Suchismita