It was October 1998 when a sensational case hit the headlines. Actor Salman Khan stood accused of killing two blackbucks and chinkara in an area near Jodhpur, Rajasthan, where he was camping for the shooting of 'Hum Saath Saath Hain'. In the vehicle with Salman at the time of the incident were Saif Ali Khan, Tabu, Neelam and Sonali Bendre. As soon as the shots rang out, the villagers were up in arms. The Bishnoi were a determined lot. To them the black buck was sacred, the incarnation of their Guru Jambeshwar.

An FIR was lodged. The case dragged on for 22 long years and even today the final verdict is nowhere in sight. (In 2018 Salman was sentenced to 5 years in jail but is out on bail after spending only two days in jail. Earlier he was was jailed for a total of 18 days in the same case in 1998, 2006 and 2007.)

The celebrities have to make court appearances at Jodhpur year after year. Consequently the importance of the Wildlife Protection Act came to be understood clearly by the film-obsessed public. In 2016 over 1700 persons involved in wildlife crimes were arrested in Rajasthan, mainly due to the efforts of the Bishnoi community.

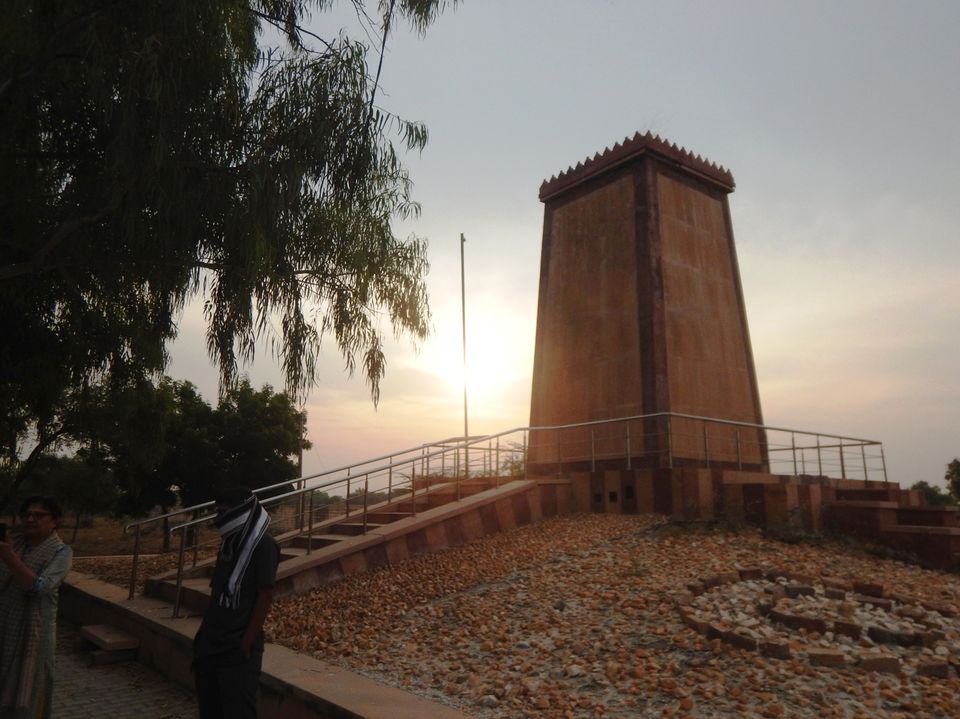

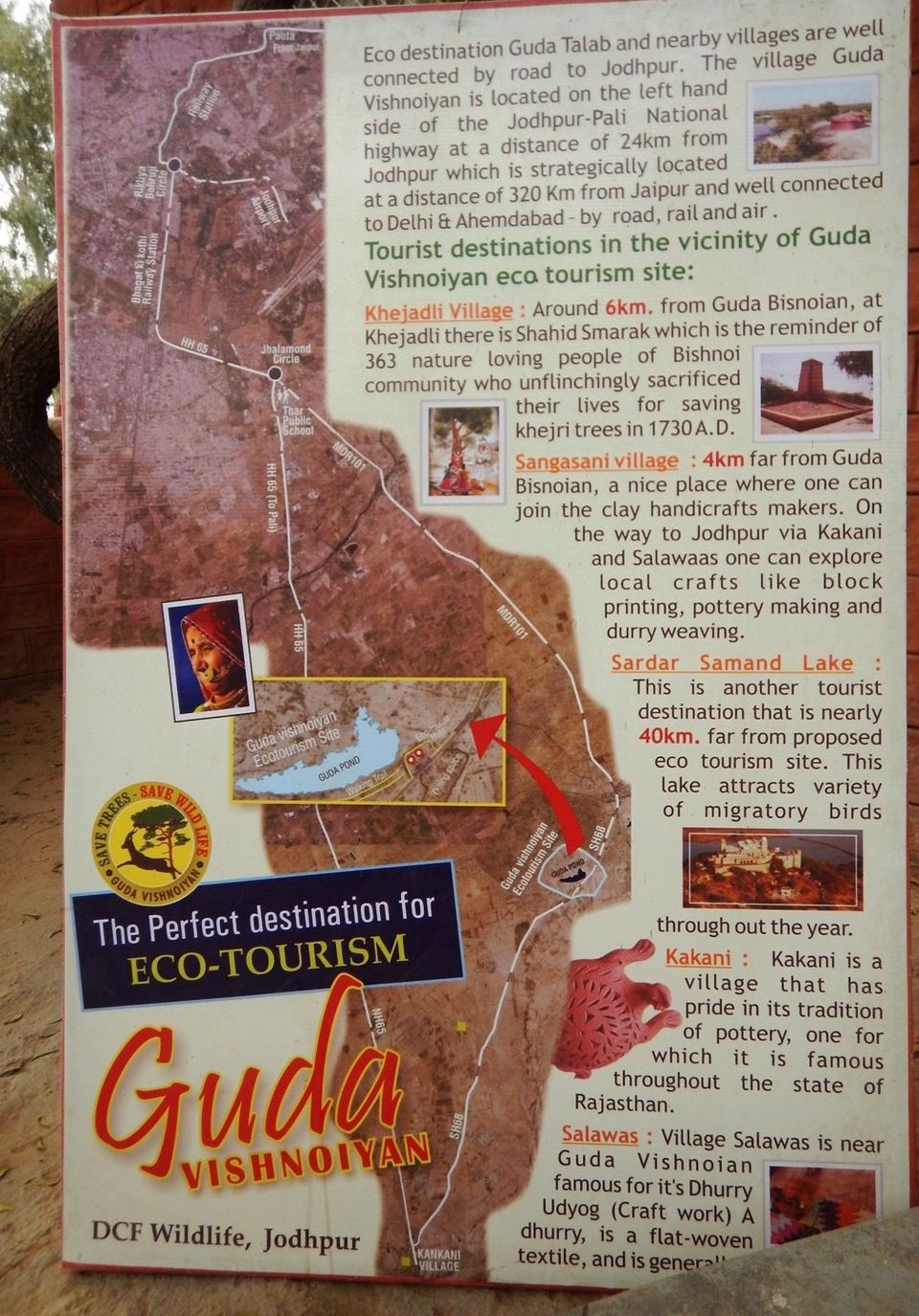

One December morning at sunrise (in 2017) my friend Lakshmi and I drove to the village of Khejarli , 26 kilometres from Jodhpur, where a humble memorial stands testimony to the supreme sacrifice of 363 Bishnoi villagers led by Amrita Devi in the year 1730. They had laid down their lives to save the khejri trees (botanical name prosopis cineraria) from the callous woodcutter’s axe.

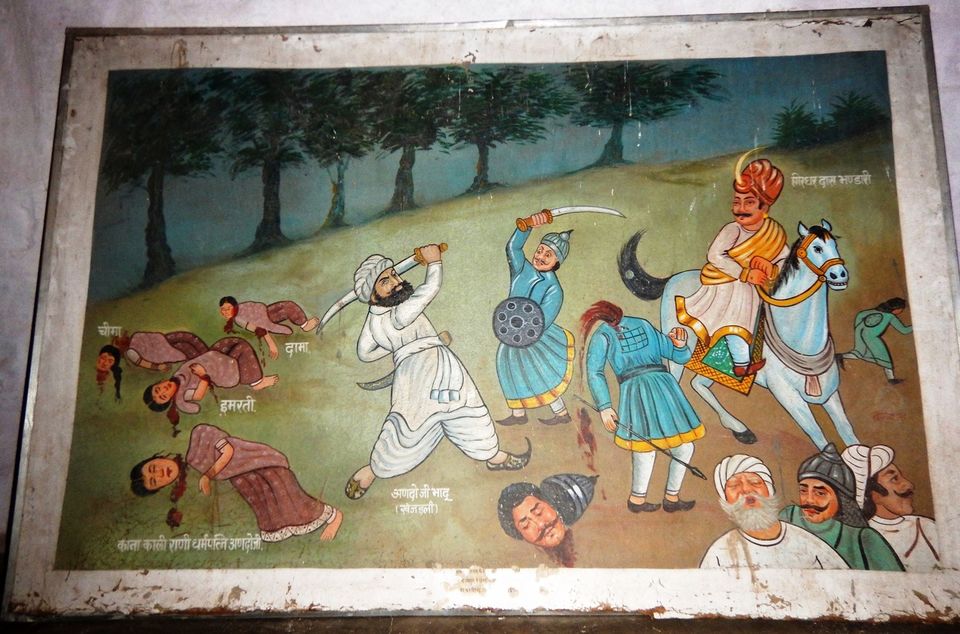

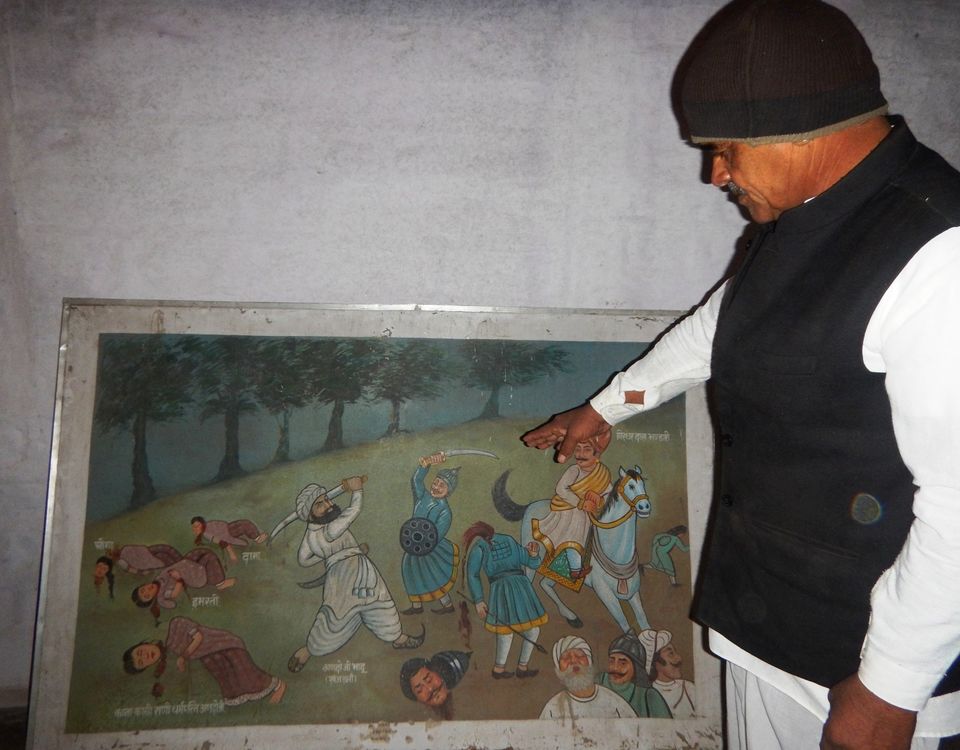

The Bishnoi had always been an environment friendly community, using only fallen twigs and branches for firewood, peacefully coexisting with birds and animals, and venerating the black buck and the khejri tree. One morning the ruler of Jodhpur sent his emissary Girdharidas Bhandari to cut down the trees in the village and bring the wood for burning. When they started cutting, the villagers gathered around and appealed to them to spare the trees. Bhandari refused. Thereupon Amrita Devi, a mother of three daughters, hugged the tree and told the men they had to kill her first. Bhandari mercilessly ordered the killing. As Amrita Devi lay dead her daughters came forward and hugged the trees – and they too were slaughtered. One after another 363 Bishnoi laid down their lives before the horrific news reached the ruler and he ordered the stopping of the carnage. The Maharaja expressed regret and issued a royal decree engraved on a copper plate forbidding the cutting of trees and hunting of animals in Bishnoi villages.

In the history of conservation there is probably no parallel to this. An entire village led by an unlettered woman and her daughters had engraved with their blood a valuable lesson on the eternal conscience of mankind. Despite their poverty and their dependence on subsistence farming they did not ravage the environment but died to protect it. Little wonder that the killing of a blackbuck in the last decade of the 20th century touched a raw nerve and elicited a strong reaction. Never mind if the offender was one of the bad-shahs of Bollywood!

The 20, 000 strong Bishnoi community had been founded in 1458 by Guru Jambeshwar who had propounded 29 principles for the people to follow. Bish-20 + Noi-9. That’s where the name comes from. Prominent among the rules are those that ensure the protection of the ecosystem and wildlife.

As we walked towards the memorial monument two elderly gentlemen accompanied us and told us the historical details. A few women appeared out of nowhere and disappeared after getting a good look at us.

We saw peacocks ambling around. They carefully moved a few steps away as we approached but didn’t disappear altogether. On the road we had seen blackbucks but there were none near the memorial. The sun was slow to rise and there was a nip in the air.

We paid our respects at the memorial where the 363 bodies had been buried. Buried, you ask? Yes buried. Unlike other Hindus, the Bishnoi don’t cremate their dead but resort to burial because wood is meant to be conserved. Living on the edge of the Thar Desert cannot be easy for anybody. I was left feeling that but for these environment-friendly practices, the desert might have encroached far beyond Jodhpur and Pali.

We moved to the small temple where a fire was burning and a man sat huddled in front of it. Our escorts showed us the paintings of the tragic massacre which were propped up against the wall. They were frayed at the edges and in need of urgent restoration. It was a sorry sight.

The men showed us the new temple that is under construction. It is magnificent but one gets the impression that the work is progressing in fits and starts. Too many pigeons had taken up residence in the interior and the floor was littered with their droppings. I asked the men whether the government was providing funds for the construction of the new building. They said no. The Bishnoi were doing it all by themselves!

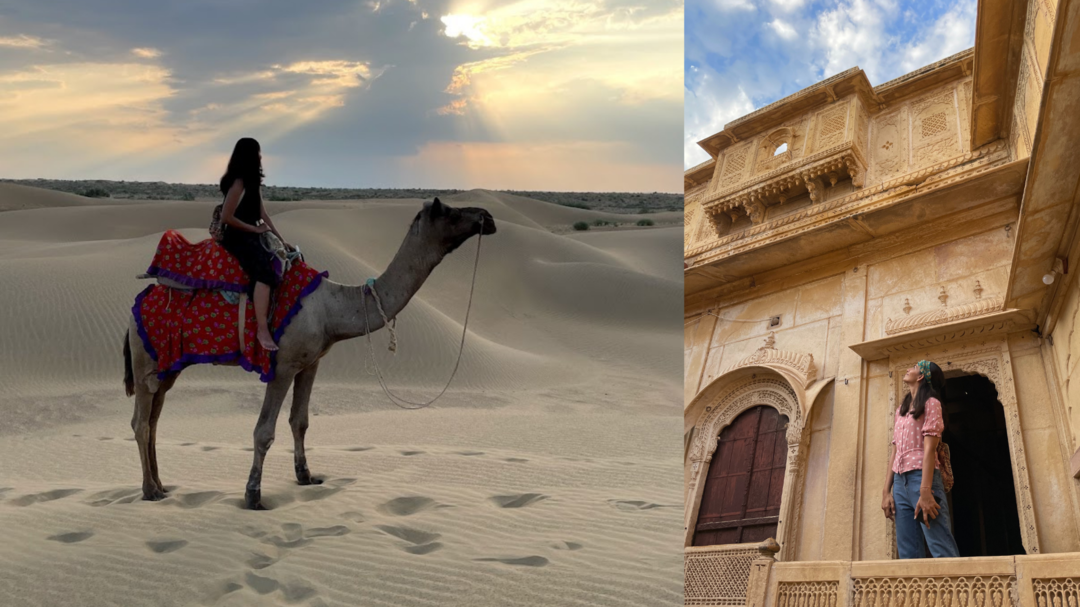

Our cab driver had a different story to tell. He expressed the view that the Bishnoi indulged in all manner of illegal activities, including opium smuggling. But I can vouch that they didn’t offer us opium tea, as they are said to do. Apparently they still grow opium. But this wasn’t the only place we heard about opium, bhang and other intoxicants. At Jaisalmer, a shop outside the fort proudly proclaimed the sale of bhang. Our guide told us that bhang lassi is widely available. So much so that when we ordered lassi we repeated “no bhang, no bhang” more than once, to the great amusement of the guide as well as the shopkeeper. Apparently the Jain merchants of western Rajasthan had made big money selling opium to Silk Road traders in the not-so-distant past, and the habit has not completely worn off.

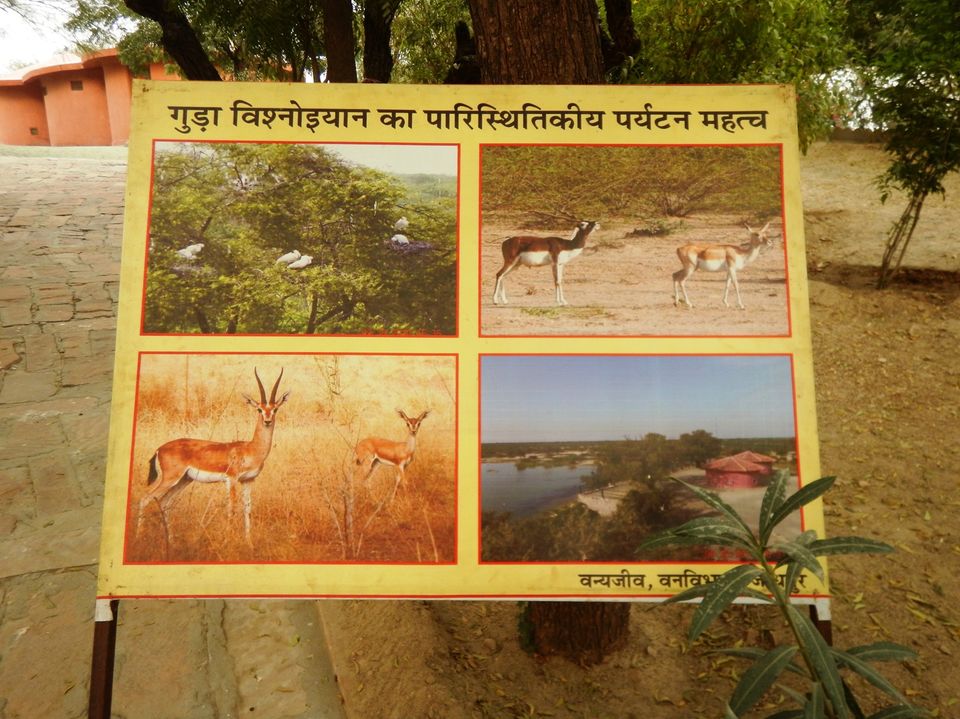

We then went to the Guda Bishnoiyan Centre where well laid out gardens and a lake welcomed us. There were hundreds of demoiselle cranes, like the ones we had seen in Khichan village on our way from Jodhpur to Jaisalmer. I guess it is unusual for migratory birds to pick such dry areas for their annual travels. It's probably the pacifism of the locals and their initiatives to feed the cranes that make the birds visit year after year.

The Bishnoi believe that the earth has sufficient resources for all her creatures. They follow what is perhaps the world's only environment-friendly religion. Above all, they recognize the right of birds, animals and trees to live in peace and harmony with homo sapiens. World leaders could learn a thing or two from the Bishnoi tribe. Madam Chief Minister might consider inviting Donald Trump to visit – minus the security cordon, of course! We don’t want to scare away the peacocks, do we?