WE MIGHT DIE

by Satu Susanna Rommi

“We might die”, says my boyfriend. “But if we don’t, it’s going to be a great experience.”

Ladakh, “the land of high passes”, is India’s sparsely populated northernmost part, surrounded by some of the highest mountains in the world. Most of Ladakh is higher than 10,000 feet above sea level, and only accessible by road for six months a year. It is a land of Tibetan Buddhist monasteries, inhabitable high altitude desert, Himalayan mountaintops and the world’s highest motorable roads.

My motorbike fanatic boyfriend and I were going to travel through Ladakh on a 500 CC Royal Enfield, the originally British motorbike that is still being manufactured in the Indian city of Chennai. The plan was to drive from Delhi to the backpacker center Manali, proceed to Ladakh’s capital Leh, and continue to the world’s highest motorable mountain pass: Khardung La. Weather and road conditions in Ladakh are unpredictable, Acute Mountain Sickness is a serious risk, fatalities involving bikers occur on Ladakh’s roads every year, yet the trip is hundreds of bikers’ dream.

Lane Driving is Sane Driving

Driving out of Delhi alone takes over an hour due to extensive road works and traffic jams, but we make it to Highway No 1 toward Chandigarh. After several previous Enfield trips around India we are already used to Indian traffic: cows and goats on the road, drunk truck drivers, and the fact that despite India’s many educative road signs such as “Lane Driving Is Sane Driving”, most of its citizens are not able to drive inside a lane.

By the time we arrive in Chandigarh, a strangely organized Indian city designed by the famous architect Le Corbusier, the Enfield’s cylinder is leaking oil, and we have to find a mechanic to change the cylinder head. We spend a night in a local hotel, where I vomit out the meal we ate earlier in a local dhaba (a cheap roadside eatery). Fortunately I stop throwing up in time for our early morning departure toward Manali. The road takes us through forests of pine, eucalyptus and wild mango trees, but unfortunately this nice mountain road is the main highway from Delhi to Himachal, and we have to fight for space with overloaded trucks, decrepit buses and cars full of holidaymakers.

The plan is to spend a couple of nights in Manali, perform a last-minute check-up on the bikes and then drive to the mountains. Instead, we end up spending several days in Manali fixing various Enfield-related problems, while it rains heavily and the road toward Leh remains closed due to a landslide. What follows is five days of watching TV, fighting over the remote control, ordering food from room service and sitting on the balcony taking photos of the mountains that are now covered in fog. When the bike is finally ready, the mountain rain has made my boyfriend sick, and I am throwing up again. We spend a few more days in our bedroom.

In The Bend, Go Slow Friend

Eventually the rain stops, the landslide is cleared away and we start the 70-odd mile drive toward Keylong, our first overnight stop. The road toward our first mountain pass, Rohtang La (13,050 feet and translated as “a pile of dead bodies”), is busy with Indian holidaymakers on their way to the pass to see snow. It is a narrow and bumpy road, sometimes covered in mud, sometimes ice cold mountain streams. Both the driver and the Enfield are working hard, while I admire the surroundings: bright green meadows covered with tiny yellow flowers, wild horses, dark forests and waterfalls, all surrounded by high mountains.

On top of the pass Indian tourists drink tea and throw snowballs at each other. In the small town of Khoksar, the local police official asks if we have any marijuana while he carefully writes down our names, passport numbers and the Enfield’s registration number; a routine to be repeated at several checkpoints on the way. By now the traffic consists mainly of trucks, while the road itself consists mainly of dust. Something falls off the bike and we discover that it is the horn: the most important part of any vehicle in a country where repetitive honking substitutes lack of driving skills.

Four and a half hours after leaving Manali, we arrive in Keylong, a small town nestled amongst high mountains, green hills and Buddhist gompas (monasteries). I notice the first signs of altitude sickness when walking ten steps to our bedroom makes me breathless.

If You Are Married, Divorce Speed

I wake up with a runny nose, while my boyfriend is suffering from severe headache, nausea and an overactive bladder. He decides to drive anyway: a bad decision and one we will regret several times.

The 75 miles we drive that day are the toughest 75 miles I have ever experienced, but come with some of the most amazing and very literally breathtaking scenery I have ever seen. The road is covered with rocks, sand, dust and leftovers from landslides. Ice-cold streams from melting glaciers run across the road. We overtake trucks right on the edge of the road next to a drop into a certain death, while trying to see the road through clouds of dust.

Never has a giant tent made out of an old parachute been as welcome a sight as on arrival at “Peace Camp”, a tent dhaba that serves simple lunches of rice, lentils and potatoes, which turns out to be the only food available from here until Leh. As the road then climbs up to Baralacha La (16,500 feet), we are surrounded by mountains that reach from barren desert towards a clear blue sky. At the top, Buddhist prayer flags decorate an otherwise moon-like landscape.

Our stop for the second night is Sarchu, a 14,000 foot high collection of tent camps. We settle inside a large parachute tent and eat a dinner of rice, dhal and potatoes. We are covered in dust, but except for a cold-water tap behind the kitchen tent, there are no washing facilities. What follows is a cold and sleepless night. My head hurts so much that just to rest it on the mattress makes me feel like it’s going to explode, and I find it increasingly difficult to breath.

Be Gentle On My Curves

The morning finally arrives, and the ladies in the kitchen tent read out the breakfast menu: omelettes with oily chapatti bread, or rice and dhal. I have no appetite. I compare our symptoms to a list of Acute Mountain Sickness symptoms in a guidebook: sleeplessness, headaches, loss of appetite, dry irritating cough, breathlessness, nausea. Between us we have all of them. Ahead of us are several high mountain passes, but turning back wouldn’t make any difference: the passes behind us are nearly as high. I swallow a headache tablet with two cups of coffee, drink plenty of water, and we move on.

A piece of advice: if struggling through deep sand on a motorbike, speed up. Don’t slow down, or you’ll fall. Which is exactly what happens to us. We fly from the bike as if from a catapult, but land in soft sand and survive with hardly a scratch. Some pushing, and the bike is back on the road.

Beep Beep, Don’t Sleep

We cross some more streams, overtake some more trucks, struggle some more in the sand and the gravel and the mud, and we reach the world’s second highest motorable pass: Taglang La, 17,582 feet. We drink sweet chai inside a small tent at the top, slightly breathless, headache creeping back.

After the pass the road descends down to another gorge and surprisingly, we end up on the best road so far. Stunning red rock formations line the road on one side, and on the other side there is a river and several charming little villages with small houses shaded by trees. In the town of Upshi we stop for coffee, incredibly dirty, dusty and sunburnt, and decide to push the last 30 miles to Leh.

We’re hoping to arrive in a nice cozy guesthouse before sunset. Instead, we spend two hours looking for a guesthouse with secure bike parking and hot showers. Exhausted, dirty, thirsty and hungry, we finally find a family-run guesthouse that promises buckets of hot water, safe parking and a laundry service.

Better To Be Mr. Late Than Late Mr.

Leh, at 11,000 feet, is the capital of Ladakh, accessible by road only from May to October. During tourist season the city is a combination of Tibetan Buddhist gompas, restaurants that serve falafel and pizza as well as Tibetan momos and thukpa, and Kashmiri souvenir stores next to Tibetan refugee markets.

By now we are bleeding from our noses every day due to a combination of sinusitis and altitude. I almost faint at dinner in a rooftop restaurant, and we visit a local doctor who thinks I have intestinal parasites as well. We spend a few days resting, eating pizza and pasta, drinking mint tea in the guesthouse’s garden and visiting Buddhist monasteries.

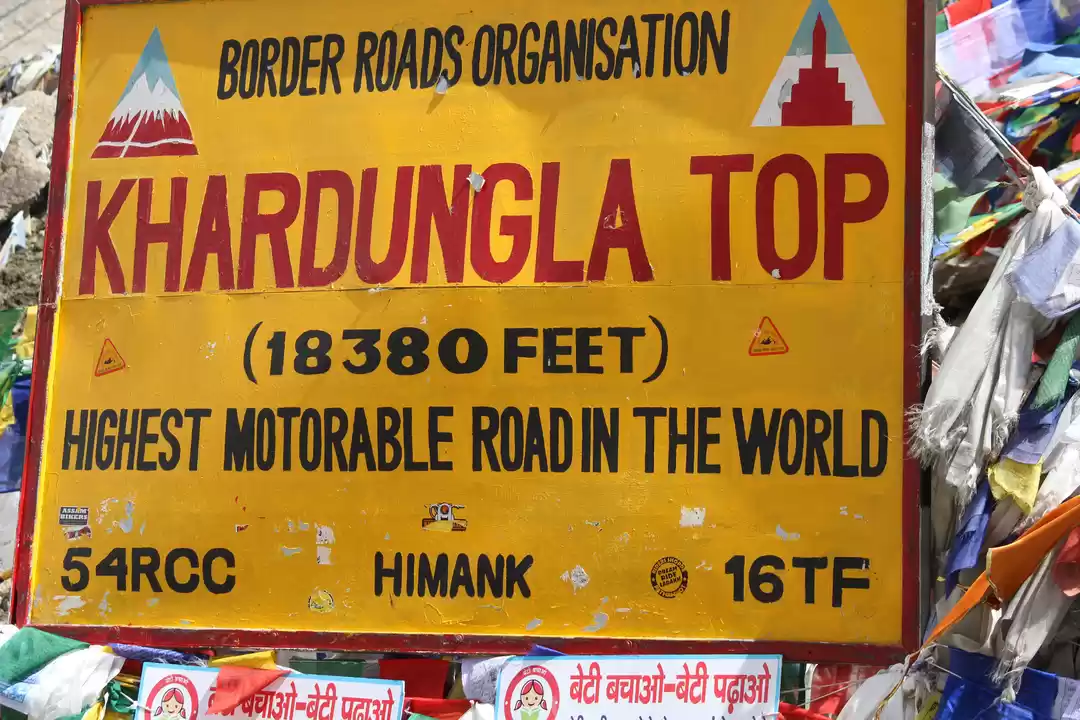

There is, however, one more pass to conquer: Khardung La, known as the world’s highest motorable pass.

Keep Your Eyes On The Road

Khardung La, or K-Top as it is affectionately known, is situated on an ancient caravan route that connected Leh to Kashgar in Central Asia. The real altitude of Khardung La is disputed due to individuals with GPS measuring much less than the official 18,380 feet, but this doesn’t really matter to most bikers who want to make it to the top.

On our way to K-Top we are blessed with beautiful sunny weather as well as a road that is covered with a rare luxury: tarmac. We arrive at K-Top breathless from the lack of oxygen, and surprised at how smooth the ride was. We drink a cup of sweet black tea at probably the highest tea stall in the world. Then we pee in what are probably the highest toilets in the world. And I forget all about the parasites and the nosebleed as we take photos of ourselves on probably the highest parking lot in the world: the highest one can get on two wheels.