The invention of the wheel was a momentous event that changed the way men travel and eventually men, not unlike the discovery of the BROKEN wheel, which changed the way we travel and eventually us.

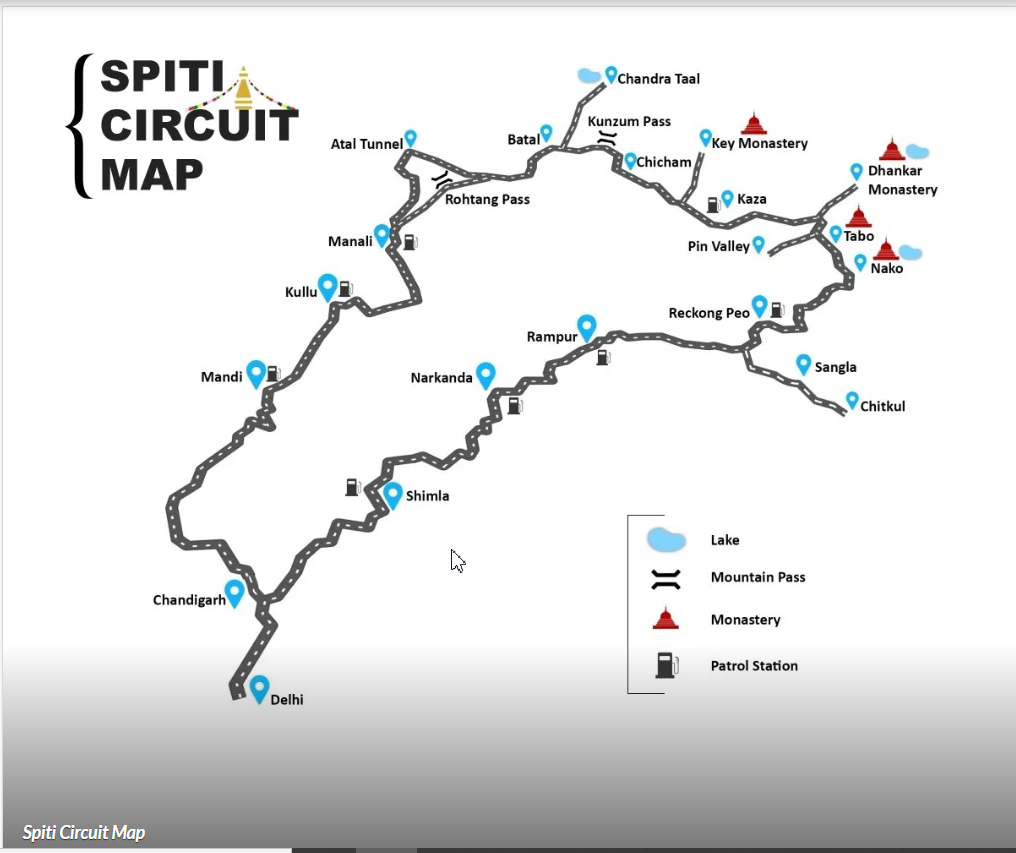

It all started with the first trip to Spiti when despite our crossed fingers and fervent prayers to the snow gods, the Kunzum Pass stayed closed. So, a second trip was arranged the next year with Kaza, Kunzum Pass and Rohtang Pass as the highlights of this 2018 trip.

The Kunzum Pass at about 4600 m on the eastern Kunzum Range connects the Lahaul and Spiti valleys in Himachal Pradesh. It opens for vehicular traffic in June-July and closes for winter in September-October. Another 75 km to the west, in the neighbourhood of Manali is the more famous Rohtang Pass (about 4000 m) in the Pir Panjal range connecting the Kullu and Lahaul valleys. Our 2018 trip would take us through both these passes and also the Chandra Taal lake, that lies en route at a detour of just 10 km.

Slowly the climb got steeper and the roads dustier as rocks and loose gravel replaced the greenery of before till finally we were at the Kunzum Pass along with about half a dozen other vehicles. The loud silence was broken only by the whistling winds and the fluttering flags that were strung about around the Kunzum Stupas. All around the pass were snow covered mountains and a few stray tufts of clouds, glowing white against a cerulean sky, while a small handful of travelers stood enchanted, staring agape, cameras forgotten, trying to take it all in. The regulars had stopped to light an incense and say a silent prayer of gratitude at the Kunzum Stupas. The roads and the lack thereof that thrills occasional travelers like us are the very ones they are at the mercy of and without a moment’s notice these roads could turn fatal. An uneventful trip was the greatest blessing that a regular traveler on these roads could ask for.

Anticipation and excitement ran high on the morning of the 19th of September, 2018, as we left Kaza, for the day long trip to Chandra Taal. After giving a ride to two cheeky kids on the way to their school, and a short breakfast halt at the beautiful, sparsely populated desert village of Losar we set off again. The breath-taking scenery with dry mountains sometimes replaced by greener pastures; tiny waterfalls crashing down the hillside, across the road, down the gorge to join the seemingly innocuous thin turquoise slip of satin far below us, the Spiti River; yaks grazing peacefully in the river valley and the bright sun painting everything in vivid colours left us speechless and spellbound.

As we alighted from the car, my son pointed out that the front passenger wheel seemed to be turned inward at an odd angle. As R and I walked away towards the stupas, Pp came around to have a look and very soon, there was a small crowd around our car.

It turned out that in the front passenger side wheel, the nut of one of the pair of nut-bolts (this set of two nut-bolts joins a wheel to the frame of a car, and is therefore indispensable for the balance and movement of a vehicle) had gone missing. As a result, the bolt was halfway out as well. One set was still intact and was what now stood between us and either a rolled-off-into-a-gorge front wheel, if we were fortunate, or rolled-off-into-a-gorge front wheel plus three other wheels plus three passengers, if we were not so fortunate.

People in tough terrains are generally helpful, including the most unhelpful city slickers. Maybe it is something about the wind and the weather or the rocks on the roads or widening of horizons that traveling forces one to go through. Everybody tried to do their bit, and finally we ended up with a nut from an Innova held to the bolt by a delicately wound wire, the wire having been sourced from a truck. The winding of the wire was a joint effort of the assembled lot. Whether it would hold or not was something time would tell. For now however, everyone had to be on their way. After bidding us all the best and informing us of Batal, a tiny settlement less than 15 km away, and, of a mechanic who is usually found there, they all left. All, but one.

This “one” was Ankit. We met him first at Mud village. He was taking a pair of honeymooners to Ladakh. In Mud village, as Pp and I were having dinner, we were joined by an Israeli traveller David on his twelfth visit to the Himalayas and Ankit. As all of us shared our stories of driving in the mountains, David told us of his reckless youth, where he had convinced a bunch of his friends to drive to Ladakh. As he passed by a ravine and happened to catch a glimpse of the remains of the cars and other vehicles that had crashed in there, most probably along with their passengers, he thought of his children back home and swore to never come back again to these treacherous terrains, only to be back the very next year and every year after that. Ankit told us of the one time he got so scared on these roads that he could not make himself drive an inch more, that is, until he spotted a convoy of half a dozen auto-riskshaws travelling to Ladakh playing “Tera Suroor”, which is when he downed some whiskey and said to himself, “If they can with three wheels, I definitely can with four” and zoomed ahead. Though I rolled my eyes inwardly, this story ensured that we were to remember Ankit for some time to come.

The next time we, or rather Pp, met Ankit, was in Kaza where Pp had gone to fill gas and check the tyres of the car before the long trip to Manali. Ankit told Pp that one of his tyres had gone bust. He had changed tyres, but that also meant that he had no stepney to rely on. He asked Pp if our cars could travel together. Pp agreed but since we were planning to leave earlier than him, Ankit asked us to go on ahead and said he would meet us later on the road.

So now, Ankit stayed back to fulfil his part of the deal, that our cars stayed together, and he was as good as his word. As Pp manoeuvred the hairpin bends at the slowest speeds possible, Ankit would travel a little further and wait till we caught up. This continued all the way till just before Batal, where he took the turn for Chandra Taal and we went straight to Batal.

Must Read: kunzum pass

The obvious remedy in such a case is to take off the tyre and attend to the wheel. However, the tyre was stuck and the lug wrench seemed to be in danger of breaking if we tried too hard. We needed to think of something else, and quick because it was afternoon already and with no human habitation around for miles, we needed to find a shelter before the deathly cold of a Himalayan night set in.

Batal is quite famous for its inhabitants, the famous Chacha-Chachi. The internet is full of stories about them, so I will not repeat. Instead I will talk about their son, Tenzin and his cousin, whose name, even though he repeated it twice I did not get, so I will call him Cousin. But before we met Tenzin and Cousin, we went to Chacha-Chachi looking for the mechanic. Chacha informed us that that he had gone off to Manali for a wedding, “his own wedding” Chachi corrected, and won’t be back before the fortnight at least. And no, they knew of no other mechanics nor had they any toolkit with them.

While we were talking thus, an HPSTC bus came in from Manali on the way to Kaza. We asked the driver and his helper if they could be of any assistance. They said, they could help ferry us tomorrow if they found us still stranded in Batal or anywhere between Batal and Manali, but that’s all they could do. No help there either.

Just as I was getting despondent and desperate, a white Tata Sumo roared in, raising a cloud of dust and in what can truly be called filmy style, two men stepped out from the cloud of dust - one wearing a leather jacket, a mohawk hat and a fancy pair of sunglasses and the other wearing shorts, a flimsy cotton tee-shirt and a Tere Naam hairstyle. The mohawk hat was Tenzin and the other was Cousin. They heard us out, checked our car and pronounced, with infectious confidence, “Forget Manali, your car is good to drive all the way to Delhi!”

Surely, they knew what they were talking about, we thought to ourselves. It was only much later that we discovered we were terribly bad judges of car-experts. But that is later. For now, we were immensely comforted by their words.

When we had discovered that the mechanic was not available, we had given up all hopes of going to Chandra Taal. Now that we knew that the next day we could be out of here, as planned, we thought quickly, and decided that we would go to Chandra Taal after all. However, we would not stay there overnight as planned, for he would leave our car here in Batal. We would make a day trip to Chandra Taal in Tenzin’s car and stay the night at Batal in one of the camps that Tenzin had set up for tourists in Batal.

We set off in the white Sumo. As Cousin drove at almost 60 kmph on the non-existent roads, Tenzin “regaled” us with stories of all the crashes that had happened in the last month or so. R was delighted at the roads and at the speed but mostly at the sheer terror on my face because nothing pleases him more than a scared mother. We reached uneventfully though and then we trekked all the way to Chandra Taal.

With its clear sky, high mountains all around, lots of mellow sunshine and all of it reflected in its clean waters, the Chandra Taal was just as beautiful as expected. There was also a group of cacophonous Bengalis fighting with their tour operator on why “machher jhol” was not available for lunch that day, which reminded me of two things, my favourite machher jhol and why we never travel with travel groups.

Beautiful as it was, we had to drive back to Batal along the narrow roads. It was not so much the thought of the roads, but rather the thought of being driven back by one of a pair of crazy drivers that made us hurry and we came back to Chandra Taal camp site/car park. Tenzin also ran a camp site there and invited us inside his tent. In typical Pahadi hospitality they got us food, my son’s favourite Maggi for him and fench toast for us. Then they sat with us, and offered us homemade barley liquor, made specially by “a friend” of theirs. The liquor was heady and potent and a little was a lot for us but seemed to have no effect on either Tenzin or Cousin. They seemed to have an endless supply of and appetite for the liquor and kept offering us as well. Since my son got bored with all this, they called a fellow with a yak and my son sat and went around the campsite, while Tenzin and his friends, with their impeccable sense of timing, further “regaled” us with tales of how yaks could never be tamed really and how dangerous riding one had turned out to be for so many people, sometimes even fatal.

Finally, with darkness fast approaching, me slightly tizzy, these two decided to leave for Batal, with a small bottle of “friend’s” barley liquor. Now Tenzin drove and he drove again at 60. One moment the road would drop off in front of us in a bottomless pit and in the next, Tenzin, from habit, would have turned a sharp left, all the while looking back and talking to us, drinking "friend's" liquor and comforting me that he could drive all the way to Manali in reverse with his eyes shut. I did not know whether to roll my eyes at his stories or keep my eyes shut in terror, but at the end of an interminable hour, we reached Batal.

It was dark and extremely cold and windy outside in the open, but the inside the tents was worse . The loud flapping and fluttering noises and the voluble Chenab flowing just outside made conversation impossible and the likelihood of being flown, tent and all, right into the Chenab, very plausible. Suffice to say, we were cold and miserable and waiting anxiously for the night to get over, till Tenzin called us to another tent where he said they had lit a bonfire.

At the thought of fire, the three of us forsook our tent and trooped into theirs. Tenzin and Cousin were sitting around a bonfire, each holding a bottle of liquor. A more welcome sight had never greeted my eyes. We quickly sat as close to the fire as possible, without being singed. The fire did to our hands and feet what the liquid fire did to our insides, and the sight of his happy parents cheered up my little hero too and very soon we were all singing, joking and laughing. There was a spicy meat dish, an appetizer, that warmed us up further and we forgot all about the chill outside, till, a couple of hours later, dinner being over, we went back to our tent again.

The tents are equipped with low beds and fleece blankets, the well-intended blankets meant to keep the cold out. However, even with all our clothes on, including mittens and mufflers and thermals and jackets, the blankets barely did their job. To add to that Pp started feeling uneasy from all the liquor and spicy food and he informed me very sombrely that Tenzin had an oxygen cylinder that Tenzin had offered Pp to use, should the need arise. For a terrifying moment I took that to mean Pp was having a heart attack and that took care of my sleep as well. As I lay shivering in my bed exhausted from a long day and worried about the next day, i decided to put away thoughts of a heart attack for now and instead I wondered if I would manage to drive an obviously ill-at-ease husband in a broken car to Manali the next if he did not feel any better by then or if it would be better to stay back and work at Chacha-Chachi’s dhaba and home-school R, till Pp felt up to it. I thought about a hundred other absurd things as well, the kinds that mill around in your head when you are about to drop the curtains on an overwhelming day.

Eventually I fell into a dreamless sleep, only to be woken, what seemed like, just five minutes later. It was daylight and we had to leave early, to ensure that we drove slowly and yet managed to reach Manali before sundown.

We said our goodbyes to whoever was up, i.e. Chachi and Chacha, and got into the car. The windscreen seemed all fogged up. We took a cloth and tried wiping it, but something seemed wrong and no matter how hard we tried, the fogginess refused to dissipate. Chachi then informed us that the windscreen was frozen and wiping it would do no good and as the day progressed, the icicles would melt on their own. Armed with this knowledge we adjusted the AC blower in the car and eventually a tiny bit cleared, the size of a keyhole, and with his eyes on the keyhole Pp started the car.

Driving with a broken car was laborious, with an iced windscreen, dangerous, and driving a broken car with an iced windscreen on loose boulders, known variously as riverbeds or roads, was unquestionably insane. Yet we ploughed on, sometimes stepping out of the car to walk across a tiny rivulet with ice cold water to let R test his Wellingtons while Pp stayed at the wheels trying to coax the repair job to hold. Meanwhile the icicles had melted, and the sunny day did make us hopeful that all would be well after all. The biggest hurdle was supposed to be Chhota Dhara. So, when we finally passed the rest house at Chhota Dhara and the car was still going strong. I heaved a sigh of relief, and, the car broke, again.

Not really broke, no. The car now got stuck on a boulder, the size of a drum. We were not being unnecessarily adventurous. The good bits of the road has large pebbles and the not-so-good bit has boulders. The smallest boulders were the size of the skull of a full grown human and the largest the size of a refrigerator. Thankfully the refrigerator sized ones were on the sides and the largest that a motorist is expected to drive over are not much larger than drums and coffee tables. As Pp tried to drive cautiously while jolting the car as less as possible, the underside of our car got stuck on one of these drum-sized rocks. No matter how much he revved the engine, the car only rocked. One of its wheels found no surface to grip and the car stayed put. There was not another soul around. The good news was that we were stuck at a very narrow point in between two refrigerator sized boulders on the Kaza Manali Highway. That meant that all traffic from both sides was no longer simply duty-bound to help us, but they would be forced to help is for if they did not manage to dislodge us, traffic would be stuck. The bad news was there was no way the delicate patchwork of wires and borrowed nuts would survive this assault. That meant that while we would definitely not be stranded at this particular spot, we would now be stranded on the roadside at another spot in the middle of nowhere.

R and I went back to the rest house to ask for help and Pp stayed with the car. The young lad at the rest house said he did not have telephone facilities and no tools with which to help us. Soon enough though two mini-vans, one from each direction made their way to our car and people jumped in to the rescue. They loaded people in the car and weighed it down and as soon as the wheel found traction, it jumped ahead and was out of the rocks. We thanked our saviours and they went their way. However, as soon as we got into the car, the banging noise immediately told us that the contraption that had held from Kunzum till Chhota Dhara was no longer in action and that the bolt and the wire were lost. We parked the car by the side on a wider portion of the road and waited.

Before long a truck stopped and then another sedan and very soon the driver of the truck and the three men from the sedan were helping Pp. it took them close to an hour, involving the spares kit from the truck and from the sedan. It also involved rocks from the roadside, mud from the river-bed, a little bit of blood, a lot of sweat and cusswords, all hallmarks of male camaraderie, the camaraderie of perfect strangers trying to fix a broken car.

Eventually it was fixed and the trucker pronounced us good to go till Delhi (yet again). We, very foolishly, tried to offer him some money for all his help, and he chided us gently asking us to pay it forward. This trucker too, like Ankit from earlier, turned out to be as good as his word, and when we did reach Manali and had it checked out by a mechanic we were told a first-class job had been done. We thanked the stars that had sent him our way on that day at that hour.

Upon our return we posted pics on Instagram and shared our travel stories with friends and family. However, what stayed with us most, of that trip were those three words, “Pay it forward”. Thinking back to the times we stopped on our way to Manali passing along bottles of water to thirsty cyclists or how, since then we have never been able to simply whoosh past stranded motorists on the Mumbai Pune Expressway as we used to earlier, I realize that the chain of events set in motion by the broken wheel has indeed changed us and hopefully for the better.

We had gone to Himachal to visit the Kunzum Pass, strut about having struck off another item from our bucket list, add a few pictures on Instagram and maybe, once in a while feel the heaviness of nostalgia and talk about “that time in Kaza…”. What we came back with was something else entirely. We came back with Knowledge, the knowledge that we are oblivious to the most obvious of truths, that everything in this universe is transient and the only thing that lasts is love; love that we show through our actions, of helping a stranger stranded on the road, of sharing food and wine around a fire on a cold night, of promising to go slow when the other cannot keep up; for love shines through the cobwebs of memories long after posts on Instagram have been pushed to the bottom and bucket lists have been shelved for good.