Ask an average Indian to name a Chinese food and you are likely to hear “chow mien-chilli chicken”. During my 10 days in China, I did not eat anything that remotely tasted like ‘chilli chicken’. And we were served rice a lot more frequently than noodles.

In southern China, rice is grown and eaten widely. It’s only in the cold north that grains like corn and wheat and dough-based food like noodles and dumplings take over. Shanxi province, for instance, produces more than 100 types of noodles.

Though the noodles preparations we had at the formal dinners tasted very different from the stuff we have here, the ‘street chow mien’ we had in Shanghai tasted surprisingly like the one we get in Kolkata. The only difference was that in Kolkata, the ingredients are predetermined depending on what you’re ordering — veg, egg, chicken or mixed chow mien. In Shanghai, we were asked to choose from a variety of chopped meat and vegetables.

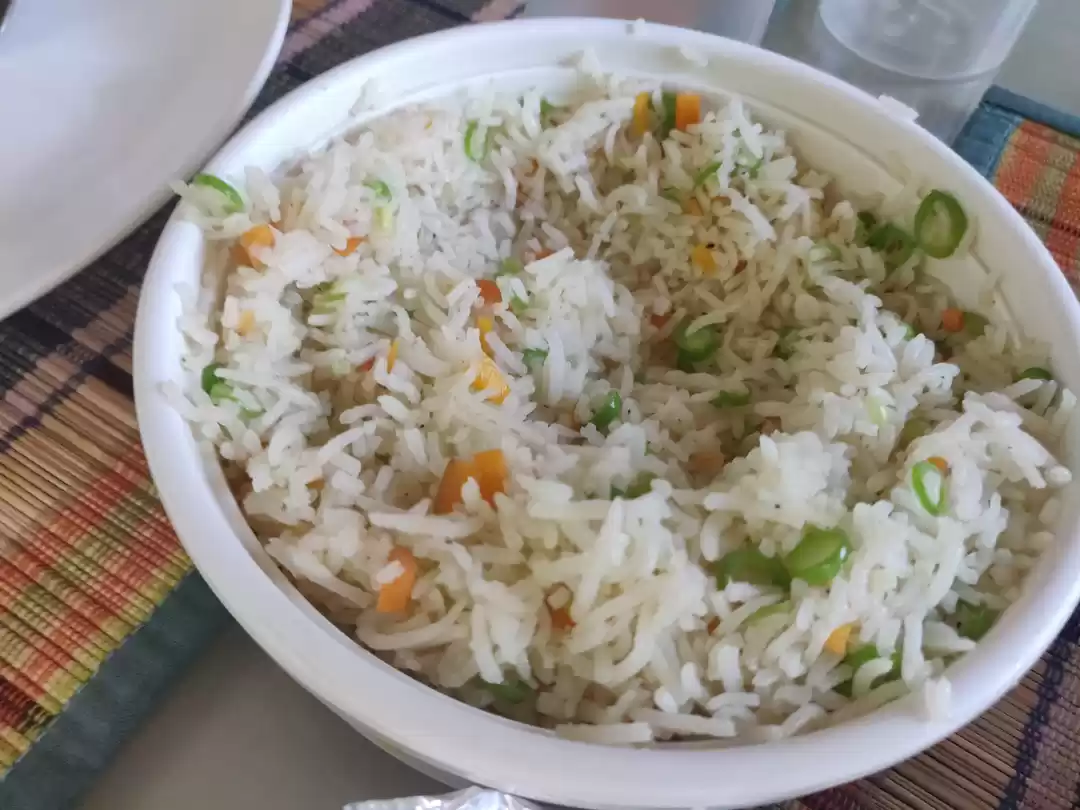

Returning to rice, the way it’s eaten is vastly different in India and China. In India, it’s the staple and everything else — dal, vegetables, fish or meat curries — is side dish. The side dishes are mixed with the rice in a plate, and eaten off it.

In China, it’s the rice that comes as a side dish (at least that’s what we were served). It’s the sticky variety that is meant to ‘soak up’ any sauce or gravy that any of the fish or meat dishes may have been cooked in. And instead of a plate, rice is eaten off a small bowl — obviously to make it easier to scoop up with chopsticks.

But this is only a minor dissimilarity. The worst comes in terms of meat. The Chinese are voracious meat-eaters. And meat mostly comprises pork and beef. And, two of India’s largest religious groups don’t eat at least either one of the two.

Worse, diners at a Chinese table keep picking their portions off the common platter through the meal. The revolving tabletop is spun round and round and people help themselves with their own chopsticks. Among Indians, this would be akin to defiling the food (jhoota).

So, if you are the orthodox kind who doesn’t even take veggies cooked in the oil in which meat (including beef/pork) was cooked or is worried sick about the food being jhoota, look for Indian restaurants in the big cities like Shanghai and Beijing. If you plan to head for the provinces, carry your own food for all the days of your trip.

Apparently, China is no country for vegetarians. On most days, I’d see a plateful of gram sprouts coming for the vegetarians of our group. Fruits would come regularly too, at the end of a meal. Tofu, bok choy (Chinese cabbage), mushroom, lotus stem or seaweeds would come every other day, potato or eggplant occasionally.

The (processed) meat preparations were mostly plain, dry dishes coming in bite-size pieces — again, possibly to make these easy to eat with chopsticks. There would usually be a dip to go with these. But there was no use of herbs or spices and hardly anything came in gravy or sauce.

One exception was the ‘hotpot’ at Datong in Shanxi. It is comparatively hot as well as sour, and suits Indian taste buds fairly well. It’s a meat-and-vegetable stew that is served on a low flame — much like a fondue. The meat can be anything — beef, pork, lamb, chicken — depending on availability I guess.

Datong seemed to be quite famous among the Chinese for its food. At the Datong hotel, we were also served a lot of ‘seafood’ — clams, oysters, whelks, prawns, squid, fish — though these are probably bred in fresh water.

We also found some strange preparations on offer at the buffet — sheep’s hooves and rabbit’s head. I took a helping of both and battled them for 10 minutes, but could not make much headway. Both were as hard as bones.

Talking of fish, however, don’t miss the Mandarin Fish in China. My first date with it was quite memorable. When the waitress put the platter down, I couldn’t stop staring. It was what looked like a whole raw fish, floating in its watery grave, looking up at me with its round mournful eyes, its little mouth curled up in a grimace.

I dolefully picked up my fork to scrape out a bit of the fish, only to get a pleasant surprise. The flesh flaked smoothly off the bones. And it was very tasty — soft, juicy and bearing a subtle flavour of the sauce that had bits of coriander leaves in it. Caution: The fish can be a bit smelly in some restaurants.

But my favourite food in China was the sweeties. The Chinese have their own version of Western pastries that are far less sweet than the Indian ones and come in some very delicate and unique flavours.

The sesame cakes of a local bakery that we found in Shanghai were delicious as well. But the best were the almond jellies that we had at a restaurant in Taiyuan. It was delightfully refreshing.

Remember one thing — don’t expect water at meals. The Chinese don’t believe in drinking cold water with their meals and one of our teammates found it out at the expense of scalding his tongue. The Chinese wash down their food with several cups of green tea.

Among drinks, I enjoyed the baijiu immensely. It’s the most popular alcoholic drink in China and has a very sweet flavour. It’s not very expensive either and comes in some pretty packages that look like vases. You can save the bottles as souvenirs.

And if you are out drinking with your Chinese friends, etiquette says you should raise a toast as many times as you possibly can. No number of ‘Cheers!’ is considered too many at a Chinese dinner.

Must-haves in China (based on my experiences in Shanghai and Shanxi)

Mandarin Fish in Shanghai

Hotpot in Datong, Shanxi

Seafood in Datong, Shanxi

Glass noodles in Shanxi

Almond jellies (available in restaurants)

Sesame cakes (available in stores as well as restaurants)

Baijiu (Fenjiu in Shanxi)