The sun rises over Asia’s largest brackish water lagoon, Chilika Lake, and boats carrying travellers set out from Mangalajodi and other villages around the lagoon, to witness a sight that was impossible to view just about some years ago. Over 5,00,000 birds – migratory and resident call this massive wetland ecosystem, their home. From a bird population of 5,000 in the 90s to a hundred times of that in 2021, this grim picture has transformed.

This is a story of how poachers and hunters became conservators.

So, what had gone wrong in Mangalajodi?

Though this ecosystem drew winged visitors from as far as Siberia, Russia, Mongolia, Central Asia, Caspian Sea, Aral Sea, Lake Baikal, and Southeast Asia, the native villagers living on its periphery did not value its significance and role in the migratory cycle.

For generations these people have lived on farming and fishing, and have been largely ignorant of concepts like environment degradation, migration, overall ecosystem balance etc. The exotic migratory bird population meant hunting and earning a premium prize for the birds.

It was regular practice to hunt birds, in his youth, and an easy earning of up to Rs. 3,000 per hunt. Incidentally the villagers also poisoned the lake plants, which when consumed by the birds would prove fatal. Despite Forest Dept and Govt crackdowns, this practice continued unabashed in the 90s.

Change of heart?

A large part of this mindset change can be attributed to the work of Nanda Kishore Bhujabal, himself a poacher, who figured out rather early in his life that the survival and thriving of these bird populations are key to the overall ecology and subsequent economy of these wetlands.

A place that was once full of birds in the 60s and 70s, was relegated to plain blank blue till the 90s. This is when Nanda realised the negative impact of this incessant hunting, and started his NGO to create awareness about saving the birds.

To get the support from the villagers, he used religious belief as a means to enrol poachers into the protection program. In 2002, he made 11 poachers vow in the name of Maa Kalijai, the local deity, that they would quit hunting. Gradually, other villagers also joined in the effort.

What was the outcome?

The birds started returning in a few years, and with them came the travellers to watch the birds. Since then, there has been a steady earning from ecotourism activities. Now the villagers work as tourist guides, assistants to the researchers and boatmen.

In September 2020, apart from the 5 lake birds recorded in Mangalajodi, the Chilika wetland registered over 11 lakh birds during the season. During the peak season, the community jointly earns upto Rs. 50,000, which is pooled back to community development.

Nanda has helped over 400 poachers quit hunting, and have found work in the various conservation projects. Today they live a much more dignified and stable life, coexisting with the birds and finding livelihood in protecting the very species that they had once hunted.

Further North, another great story is in the making

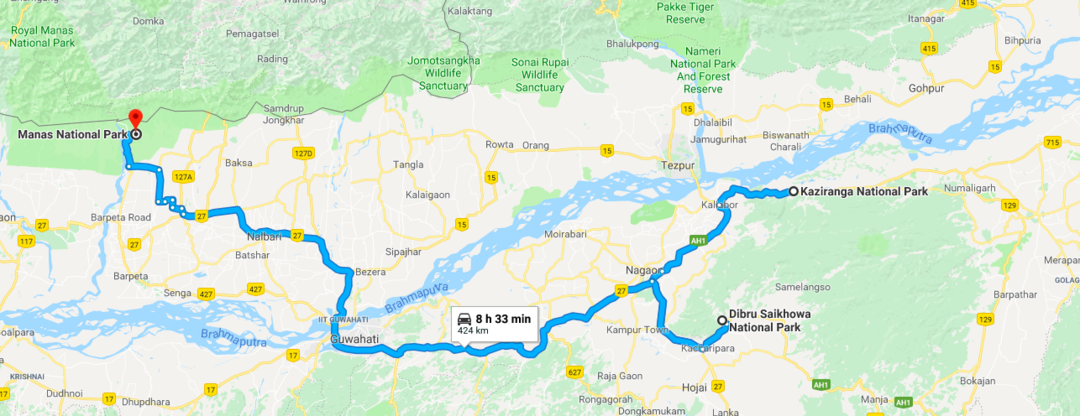

1,400 kms northwards, another conservation story has brought back the national animal to the forests of North East India. In the last decade, the Manas National Park in Assam has seen a three fold increase in the tiger population, from 16 in 2010 to 52 in the last census. What give the tiger conservationists another reason to cheer is that three tigers were spotted at the park's newly-added 360 sq km "first addition" tiger habitat.

What had happened to the tigers?

The Manas National Park faced the brunt of the territorial Bodoland scuffle in the 80s and 90s, as per news reports. Once the Bodoland Territorial Council was created in 2000s, local community organisations were encouraged by park managers and the BTC administration to safeguard the park's sanctity and reinstate its past glory. The fauna had faced a massive blow due to the conflict, the rhinos becoming extinct and the tiger population had dwindled severely.

How did the tigers return?

Local participation, government support and NGO work together contributed to the recovery of the ecosystem and the reinstatement of the count of prey animals including the tiger. Today both the local administrative bodies and NGOs draw pride from having helped regain the lost glory of Manas National Park which is a World Heritage site, a Tiger Reserve and a Biosphere Reserve.

Both these stories are heartening to hear, and speak a lot about the role of local populations in safeguarding and conserving the wildlife pockets that remain in India.

Follow me on Tripoto and Instagram @thewanderjoy for more travel and life adventures!

Earn credits and travel for free with Tripoto's weekend getaways, hotel stays and vacation packages!

Get travel inspiration from us daily! Save our number and send a Whatsapp message on 9599147110 to begin!